Videos

Video Version (In Multiple Uploads)

- Full Video (151 min)

- Part 1: Reactions & Commentary (37 min)

- Part 2: Conclusions After Research (10 min)

- Appendix A: Quotes & Notes from Mask Studies (55 min)

- Appendix B: Summaries of Mask Studies (5 min)

- Appendix C: A Familiar Meme (3 min)

[Trailer] MIT study finds anti-maskers are “grounded in a more scientific rigor”

4 min: https://tinyurl.com/4n9445vj

[FULL Reactions+Research] MIT study finds anti-maskers are “grounded in a more scientific rigor”

151 min: https://tinyurl.com/ur3s8uuh

[Reactions+Research Conclusions] (Parts 1+2)

48 min: https://tinyurl.com/r8t59ypk

[Research Conclusions] (Part 2)

11 min: https://tinyurl.com/rn6ffsd2

[Research Notes] (Appendix A+B)

61 min: https://tinyurl.com/kvk8d467

[Familiar CDC Meme] (Appendix C)

3 min: https://tinyurl.com/pke3atbk

Full Essay

Introduction

Introduction

“Most fundamentally, the groups we studied believe that science is a process, and not an institution.”

A team from MIT put together a fascinating study on online research communities. I loved reading it and wanted to share with others to help them try to understand my world. Some of the research communities they studied sounded adjacent to independent research and media communities that I have participated in since before the 2009 Swine Flu Pandemic. This study also provides some fascinating lenses on my work in progress at buckystats.org.

As a software engineer who wants collective decisions to be more evidence-based, especially wherever informed consent is likely to be violated, this study was very fun to read. I only have a B.S. from the University of Maryland in 2005 for Computer Science with a concentration in Mathematics, through the Science, Technology, & Society Scholars program. I’ve been a public health activist since age nine with my first decade focused on big tobacco’s targeting of children. My second decade focused on ending the devastating war on drugs, where public health issues continue to be unjustly treated as criminal issues.

I do not claim this is a rigorous scientific inquiry, but rather, a rigorous dive into the resources and rhetoric cited in the 2021 MIT study first brought to my attention by The Last American Vagabond. Thanks you for all your work, Ryan!

This article began as a subjective reaction to the MIT study, written to share with others to help them understand. But as I began digging into the literature cited, it grew into a more objective review on the sub-topic of evidence for the efficacy of universal mask mandates.

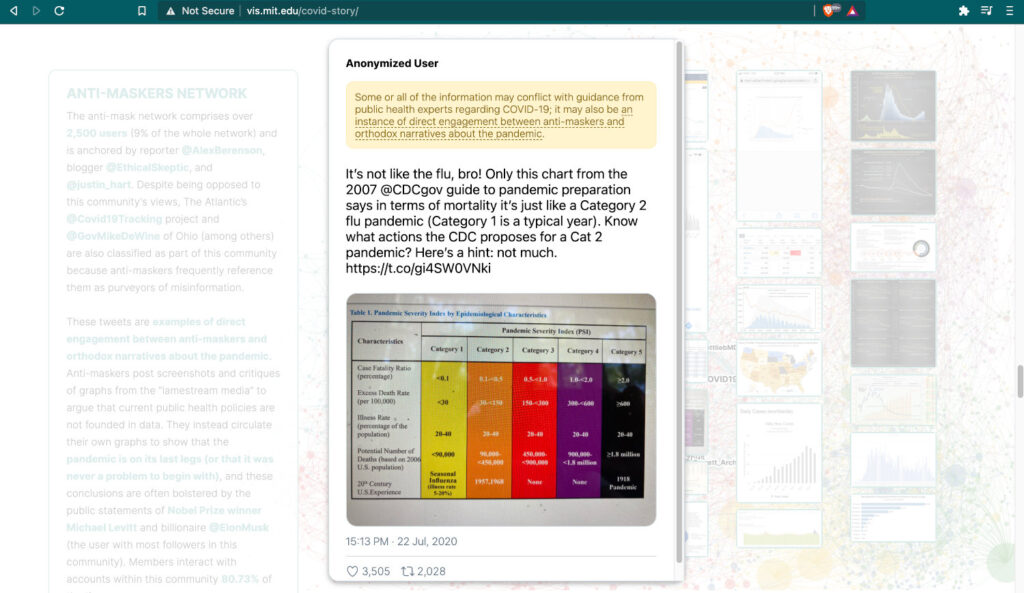

Please find below the 2021 MIT study titled “Viral Visualization: How Coronavirus Skeptics Use Orthodox Data Practices to Promote Unorthodox Science Online.” I have pulled quotes in sequential order and included page numbers from the study for you to reference. Throughout this article, I pivot from the study to my own running analysis throughout, and I welcome your engagement and discussion.

Discussing The New MIT Study

Viral Visualizations: How Coronavirus Skeptics Use Orthodox Data Practices to Promote Unorthodox Science Online (May 2021, PDF, Explainer Video, Interactive)

https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3411764.3445211

Epistemological Rifts

“ABSTRACT: Controversial understandings of the coronavirus pandemic have turned data visualizations into a battleground. Defying public health officials, coronavirus skeptics on US social media spent much of 2020 creating data visualizations showing that the government’s pandemic response was excessive and that the crisis was over. This paper investigates how pandemic visualizations circulated on social media, and shows that people who mistrust the scientific establishment often deploy the same rhetorics of data-driven decision-making used by experts, but to advocate for radical policy changes. Using a quantitative analysis of how visualizations spread on Twitter and an ethnographic approach to analyzing conversations about COVID data on Facebook, we document an epistemological gap that leads pro- and anti-mask groups to draw drastically different inferences from similar data. Ultimately, we argue that the deployment of COVID data visualizations reflect a deeper sociopolitical rift regarding the place of science in public life.”

Page 1

Who is advocating for radical policy changes? From my perspective, a year of universal community mask mandates is a very radical policy change. “Anti-maskers” simply support the pre-2020 established social norms as well as the pre-2020 scientific paradigm regarding potential mask mandate efficacy. But the MIT study dives in…

“While previous literature in visualization and science communication has emphasized the need for data and media literacy as a way to combat misinformation [43, 47, 89], this study finds that anti-mask groups practice a form of data literacy in spades. Within this constituency, unorthodox viewpoints do not result from a deficiency of data literacy; sophisticated practices of data literacy are a means of consolidating and promulgating views that fly in the face of scientific orthodoxy. Not only are these groups prolific in their creation of counter-visualizations, but they leverage data and their visual representations to advocate for and enact policy changes on the city, county, and state levels.

Page 2-5

…

We define this counterpublic’s visualization practices as “counter-visualizations” that use orthodox scientific methods to make unorthodox arguments, beyond the pale of the scientific establishment. Data visualizations are not a neutral window onto an observer-independent reality; during a pandemic, they are an arena of political struggle.

…

These findings suggest that the ability for the scientific community and public health departments to better convey the urgency of the US coronavirus pandemic may not be strengthened by introducing more downloadable datasets, by producing “better visualizations” (e.g., graphics that are more intuitive or efficient), or by educating people on how to better interpret them. This study shows that there is a fundamental epistemological conflict between maskers and anti-maskers, who use the same data but come to such different conclusions. As science and technology studies (STS) scholars have shown, data is not a neutral substrate that can be used for good or for ill [14, 46, 84]. Indeed, anti-maskers often reveal themselves to be more sophisticated in their understanding of how scientific knowledge is socially constructed than their ideological adversaries, who espouse naive realism about the “objective” truth of public health data. Quantitative data is culturally and historically situated; the manner in which it is collected, analyzed, and interpreted reflects a deeper narrative that is bolstered by the collective effervescence found within social media communities. Put differently, there is no such thing as dispassionate or objective data analysis. Instead, there are stories: stories shaped by cultural logics, animated by personal experience, and entrenched by collective action. This story is about how a public health crisis—refracted through seemingly objective numbers and data visualizations—is part of a broader battleground about scientific epistemology and democracy in modern American life.

…

There is a temptation in studies of this nature to describe these groups as “anti-science,” but this would make it completely impossible for us to meaningfully investigate this article’s central question: understanding what these groups mean when they say “science.”

…

By comparing the visualizations shared within anti-mask and mainstream networks, we discover that there is no significant difference in the kinds of visualizations that the communities on Twitter are using to make drastically different arguments about coronavirus (figure 3). Antimaskers (the community with the highest percentage of verified users) also share the second-highest number of charts across the top six communities (table 1), are the most prolific producers of area/line charts, and share the fewest number of photos (memes and images of politicians; see figure 3).

…

This leads us to an interpretive question that animates the Facebook analysis: how can opposing groups of people use similar methods of visualization and reach such different interpretations of the data? We approach this problem by ethnographically studying interactions within a community of anti-maskers on Facebook to better understand their practices of knowledge-making and data analysis, and we show how these discussions exemplify a fundamental epistemological rift about how knowledge about the coronavirus pandemic should be made, interpreted, and shared.”

Yes, very well done! One fundamental epistemological rift could separate people who no longer take institutional data and interpretation at face value or as unquestionable gospel. A subset of that rift might only feel that way regarding totally novel situations with totally inadequate data. Another rift might only find scientific experiments compelling if they have a control arm. Another rift might simply consider the successful replication of experiments to be a minimum prerequisite to building “evidence-based” public policy. Many of us are just pointing out the extreme levels of uncertainty, and declaring that we do not consider the data and/or logic as very actionable — especially not for life-and-death decisions.

Another epistemological rift is happy to make public policy based on a couple of novel studies which “suggest” something “might” have some effect. A subset of them do not need to see any studies on the potential consequences of the policy. But to my mind, heart, and gut… in many cases, the best conclusions are still far too uncertain to ethically threaten people with fines, jail, and/or a state-sanctioned demolition of their small businesses, livelihoods, or personal passions.

It seems the most publicized public health experts are more than happy to support public policies that have as much peer-reviewed evidence as a click-bait headline.

“These statistics suggest that anti-maskers tend to be among the most prolific sharers of data visualizations on Twitter, and that they overwhelmingly amplify these visualizations to other users within their network (88.97% of all retweets are in-network).”

Page 10

I don’t know if Twitter was shadow banning people this past year, as often occurs in Facebook and YouTube algorithms. But countless posts were flagged as potential misinformation, and user accounts were deleted. This further compacted the antimasker network’s footprint remaining on each platform last year. This might be an unacknowledged factor in the high percentage.

“For these anti-mask users, their approach to the pandemic is grounded in a more scientific rigor, not less.

Page 12-15

4.2.6 Developing expertise and processes of critical engagement.

The goal of many of these groups is ultimately to develop a network of well-informed citizens engaged in analyzing data in order to make measured decisions during a global pandemic.

…

The discussion-based nature of these Facebook groups also give these followers a space to learn and adapt from others, and to develop processes of critical engagement.

…

These individuals as a whole are extremely willing to help others who have trouble interpreting graphs with multiple forms of clarification: by helping people find the original sources so that they can replicate the analysis themselves, by referencing other reputable studies that come to the same conclusions, by reminding others to remain vigilant about the limitations of the data, and by answering questions about the implications of a specific graph. The last point is especially salient, as it surfaces both what these groups see as a reliable measure of how the pandemic is unfolding and what they believe they should do with the data. These online communities therefore act as a sounding board for thinking about how best to effectively mobilize the data towards more measured policies like slowly reopening schools. “You can tell which places are actually having flare-ups and which ones aren’t,” one user writes. “Data makes us calm.” (July 21, 2020)

Additionally, followers in these groups also use data analysis as a way of bolstering social unity and creating a community of practice. While these groups highly value scientific expertise, they also see collective analysis of data as a way to bring communities together within a time of crisis, and being able to transparently and dispassionately analyze the data is crucial for democratic governance. In fact, the explicit motivation for many of these followers is to find information so that they can make the best decisions for their families—and by extension, for the communities around them.

…

The message that runs through these threads is unequivocal: that data is the only way to set fear-bound politicians straight, and using better data is a surefire way towards creating a safer community.

DISCUSSION

Anti-maskers have deftly used social media to constitute a cultural and discursive arena devoted to addressing the pandemic and its fallout through practices of data literacy. Data literacy is a quintessential criterion for membership within the community they have created. The prestige of both individual anti-maskers and the larger Facebook groups to which they belong is tied to displays of skill in accessing, interpreting, critiquing, and visualizing data, as well as the pro-social willingness to share those skills with other interested parties. This is a community of practice [63, 102] focused on acquiring and transmitting expertise, and on translating that expertise into concrete political action. Moreover, this is a subculture shaped by mistrust of established authorities and orthodox scientific viewpoints. Its members value individual initiative and ingenuity, trusting scientific analysis only insofar as they can replicate it themselves by accessing and manipulating the data firsthand. They are highly reflexive about the inherently biased nature of any analysis, and resent what they view as the arrogant self-righteousness of scientific elites.

…

The counter-visualizations that they produce and circulate not only challenge scientific consensus, but they also assert the value of independence in a society that they believe promotes an overall de-skilling and dumbing-down of the population for the sake of more effective social control [39, 52, 98]. As they see it, to counter-visualize is to engage in an act of resistance against the stifling influence of central government, big business, and liberal academia.

…

Most fundamentally, the groups we studied believe that science is a process, and not an institution. As we have outlined in the case study, these groups mistrust the scientific establishment (“Science”) because they believe that the institution has been corrupted by profit motives and politics. The knowledge that the CDC and academics have created cannot be trusted because they need to be subject to increased doubt, and not accepted as consensus. In the same way that climate change skeptics have appealed to Karl Popper’s theory of falsification to show why climate science needs to be subjected to continuous scrutiny in order to be valid [42], we have found that anti-mask groups point to Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions to show how their anomalous evidence— once dismissed by the scientific establishment—will pave the way to a new paradigm … For anti-maskers, valid science must be a process they can critically engage for themselves in an unmediated way. Increased doubt, not consensus, is the marker of scientific certitude.

Arguing that anti-maskers simply need more scientific literacy is to characterize their approach as uninformed and inexplicably extreme. This study shows the opposite: users in these communities are deeply invested in forms of critique and knowledge production that they recognize as markers of scientific expertise. If anything, anti-mask science has extended the traditional tools of data analysis by taking up the theoretical mantle of recent critical studies of visualization [31, 35]. Anti-mask approaches acknowledge the subjectivity of how datasets are constructed, attempt to reconcile the data with lived experience, and these groups seek to make the process of understanding data as transparent as possible in order to challenge the powers that be.

…

We argue that the anti-maskers’ deep story draws from similar wells of resentment, but adds a particular emphasis on the usurpation of scientific knowledge by a paternalistic, condescending elite that expects intellectual subservience rather than critical thinking from the lay public.

…

Convincing anti-maskers to support public health measures in the age of COVID-19 will require more than “better” visualizations, data literacy campaigns, or increased public access to data. Rather, it requires a sustained engagement with the social world of visualizations and the people who make or interpret them.“

(More on dumbing us down: The Ultimate History Lesson)

With any novel topic explored by science, there should not be any public ‘consensus’ about scientific findings yet. That itself is already ‘anti-science’. Knowledge on new topics is constantly in flux and we’ve barely identified the first batch of known unknowns related to most of 2020.

This is part of the epistemological rift: many seem content to quickly believe a brand new scientific paradigm and consensus which cannot possibly have enough verified evidence to support it yet. It seems one of the biggest flaws in this study is its assumption that “anti-maskers” are indeed generally wrong and have an “unorthodox” analysis of “a preponderance of evidence.” But in reality, most evidence suggests little-to-no effect.

Unorthodox Positions Citing Orthodox Institutions

Nonpharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs)

Public health studies specific to SARS-CoV-2 only emerged in 2020. So most previous studies focused on influenza-like illnesses, and occasionally SARS or MERS. At the start of this pandemic — and declarations of consensus of “the science” — there were decades of studies regarding masks and influenza-like illnesses. (In Appendix A, I poke the most obvious holes in the experimental designs of almost every new study on SARS-CoV-2, as I see them.)

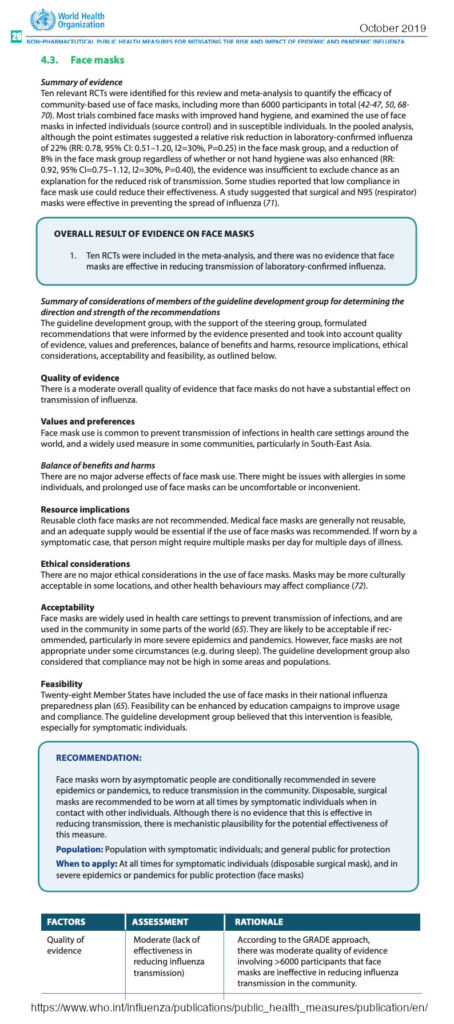

This January 2021, I found this guidance that the World Health Organization (WHO) published in October 2019 titled, “Non-pharmaceutical public health measures for mitigating the risk and impact of epidemic and pandemic influenza.” (PDF) The ‘available evidence’ section of the executive summary states that:

“… the evidence base on the effectiveness of NPIs in community settings is limited, and the overall quality of evidence was very low for most interventions. There have been a number of high quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrating that personal protective measures such as hand hygiene and face masks have, at best, a small effect on influenza transmission, although higher compliance in a severe pandemic might improve effectiveness. However, there are few RCTs for other NPIs, and much of the evidence base is from observational studies and computer simulations.”

Page 8

“There is also a lack of evidence for the effectiveness of improved respiratory etiquette and the use of face masks in community settings during influenza epidemics and pandemics.”

Page 10

“Ten relevant RCTs were identified for this review and meta-analysis to quantify the efficacy of community-based use of face masks, including more than 6000 participants in total (42-47, 50, 68-70). Most trials combined face masks with improved hand hygiene, and examined the use of face masks in infected individuals (source control) and in susceptible individuals.

Page 32, WHO Guidance on Pandemic NPIs, 2019

…

Ten RCTs were included in meta-analysis, and there was no evidence that face masks are effective in reducing transmission of laboratory-confirmed influenza.“

.

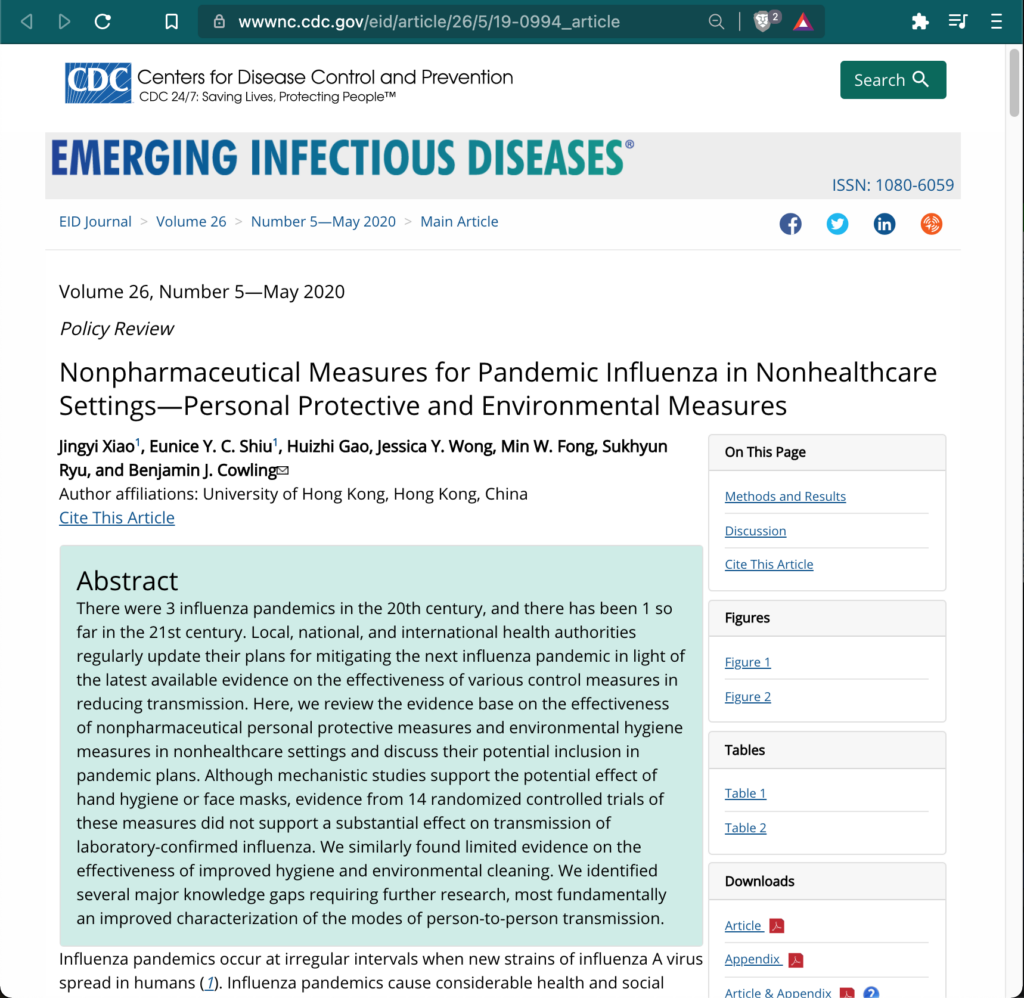

In May 2020, I found the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) policy review published earlier in May titled, “Nonpharmaceutical Measures for Pandemic Influenza in Nonhealthcare Settings—Personal Protective and Environmental Measures.” The abstract states:

“Although mechanistic studies support the potential effect of hand hygiene or face masks, evidence from 14 randomized controlled trials of these measures did not support a substantial effect on transmission of laboratory-confirmed influenza. We similarly found limited evidence on the effectiveness of improved hygiene and environmental cleaning. We identified several major knowledge gaps requiring further research, most fundamentally an improved characterization of the modes of person-to-person transmission.”

The CDC’s methods and results section explains:

“In our systematic review, we identified 10 RCTs that reported estimates of the effectiveness of face masks in reducing laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infections in the community from literature published during 1946–July 27, 2018. In pooled analysis, we found no significant reduction in influenza transmission with the use of face masks (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.51–1.20; I2 = 30%, p = 0.25) (Figure 2).

….

Most studies were underpowered because of limited sample size, and some studies also reported suboptimal adherence in the face mask group.

…

There is limited evidence for their effectiveness in preventing influenza virus transmission either when worn by the infected person for source control or when worn by uninfected persons to reduce exposure. Our systematic review found no significant effect of face masks on transmission of laboratory-confirmed influenza.“

The CDC’s discussion section reiterates:

“In this review, we did not find evidence to support a protective effect of personal protective measures or environmental measures in reducing influenza transmission. Although these measures have mechanistic support based on our knowledge of how influenza is transmitted from person to person, randomized trials of hand hygiene and face masks have not demonstrated protection against laboratory-confirmed influenza, with 1 exception (18).

…

We did not find evidence that surgical-type face masks are effective in reducing laboratory-confirmed influenza transmission, either when worn by infected persons (source control) or by persons in the general community to reduce their susceptibility (Figure 2).”

These two systematic reviews by the WHO in October 2019 and the CDC in May 2020 clearly confirmed that at the beginning of this pandemic we did not have compelling evidence to support the unprecedented public health policies. At the same time, an unquestionable ‘consensus’ had already been declared through the birth of the Post-2020 paradigms.

To empathize more with minds like mine…

Imagine reading in CDC’s May policy review that “14 randomized controlled trials of these measures did not support a substantial effect on transmission of laboratory-confirmed influenza,” and then feeling gaslit and censored for a straight year by the CDC.

Moving Forward, Together

Moving forward, why would we the [skeptical] people trust the judgment of those claiming consensus before there even existed compelling evidence? How many deceptions must we tolerate ‘for national security,’ with past violations compounding instead of justice being restored? It’s really a sick joke in a sad clown world, and given how little control we have over it, it’s usually more fun to laugh than cry about it… in between reading the documents and data, and tending the garden!

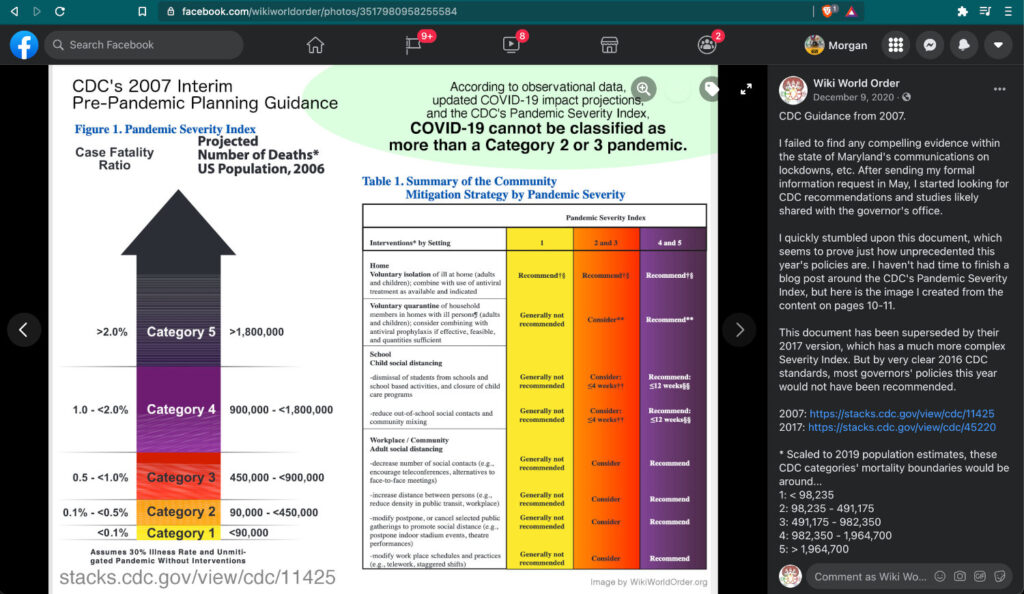

The CDC and WHO were speaking out of both sides of their overlapping mouths, recommending public policies for which they found little-to-no evidence. As acknowledged in this MIT study, Anthony Fauci admitted in June that he [misled or] lied to the public in March 2020 for reasons not disclosed to the public until later. (This was a compartmentalized intelligence operation.) He says the circumstances changed — but he’s talking about the mask supply, not the science. All of this directly contributed to a further implosion of trust in institutions that require pre-existing trust to be most effective. The fog of war creates such extreme problems, civilian causalities, and profit incentives. So declaring wars is rarely an effective or moral solution for anything.

“We’re at war. In a true sense, we’re at war, and we’re fighting an invisible enemy.”

Trump, 3/22/2020

“Look, we know what we need to do to beat this virus: Tell the truth. Follow the scientists and the science. Work together. Put trust and faith in our government to fulfill its most important function, which is protecting the American people — no function more important.

Biden, 3/11/2020 (transcript)

…

That’s why I’m using every power I have as President of the United States to put us on a war footing to get the job done. It sounds like hyperbole, but I mean it: a war footing.”

“Either you are with us, or you are with the terorrists.”

Bush, 9/21/2001

“We must speak the truth about terror. Let us never tolerate outrageous conspiracy theories.”

Bush, 11/10/2001

Given that universal community mask mandates are a new and sudden scientific paradigm, how and when exactly was that debate “ended”? What was the trick used to turn “no significant effect” into “a preponderance of evidence” supporting an effect?

.

First, the institutions say that laypeople cannot effectively understand scientific concepts and literature. Even though these topics have taken over almost all political decisions, we must outsource almost all of our thinking to “trust the experts.” Established institutions try to ensure that we only hear from their favorite <20% of credentialed experts. And they close the trap by declaring a consensus before compelling data had been collected, let alone experiments replicated and uncertainties verified.

(When the U.S. government used new data models last spring, some claim: “The data projections shared were neither peer-reviewed, nor submitted to the Federal Register to initiate a 60-day public comment period as required by law. As a result, the OMB was not able to approve the use of these projections, which makes their use by any federal agency, for any reason, illegal.“)

Better visualizations and sustained engagement will never replace a void in actionable data used to strong-arm a population. But I would be ecstatic for establishment ‘consensus’ institutions to directly engage with the ‘skeptics.’ Half the time, that would be enough to feel heard. We and our favorite credentialed experts are increasingly censored and/or targeted with mass-media smear campaigns. Fact-checking efforts rarely check more than straw men arguments.

Instead, we should try putting some of the strongest ‘skeptic’ experts up against some of the strongest institutionally favored experts in a series of long-form debates. Despite its limited Overton window, I’ve enjoyed the model of Intelligence Squared U.S. for over a decade. When strong data points collapse given more compelling evidence, any critical thinkers trying to increase their certainty will quickly abandon those positions.

“While academic science is traditionally a system for producing knowledge within a laboratory, validating it through peer review, and sharing results within subsidiary communities, anti-maskers reject this hierarchical social model. They espouse a vision of science that is radically egalitarian and individualist. This study forces us to see that coronavirus skeptics champion science as a personal practice that prizes rationality and autonomy; for them, it is not a body of knowledge certified by an institution of experts.”

Page 15

From the perspective of my favorite research communities, this point is also not quite right. Peer review studies can be great, and we frequently cite them to strengthen our understandings and claims. But dishonest declarations of ‘consensus’ sully the good name and great value of the scientific method.

I do not see the hierarchical social model of peer review as inherently wrong or bad. I am simply aware of chronic corruption by the flows of funding. There are quantifiable crises in science that breed valid skepticism for many existing institutions and processes. It’s harder to tease out bad actors when groupthink infects almost every institution. But suspect behavior is often quite identifiable and can be much more targeted than hastily generalizing to ‘all hierarchical’ scientific review.

“A secondary issue is one of uncertainty: Jessica Hullman and Zeynep Tufekci (among others) have both showed how not communicating the uncertainty inherent in scientific writing has contributed to the erosion of public trust in science [56, 99]. As Tufekci demonstrates (and our data corroborates), the CDC’s initial public messaging that masks were ineffective—followed by a quick public reversal— seriously hindered the organization’s ability to effectively communicate as the pandemic progressed. As we have seen, people are not simply passive consumers of media: anti-mask users in particular were predisposed to digging through the scientific literature and highlighting the uncertainty in academic publications that media organizations elide. When these uncertainties did not surface within public-facing versions of these studies, people began to assume that there was a broader cover-up [98].

Page 16

But as Hullman shows, there are at least two major reasons why uncertainty hasn’t traditionally been communicated to the public [54]. Researchers often do not believe that people will understand and be able to interpret results that communicate uncertainty (which, as we have shown, is a problematic assumption at best).”

I’ve long shared the view that far more expert debates are appropriate for representative governance in such a complex society. Even if most people aren’t interested, these would help clarify the public understandings closest to academia and independent media outlets. You must also convince the people who are actually questioning and researching the issues.

But instead of hosting debates, the establishment ‘consensus’ just smears ‘skeptical’ experts and literally censors those who share peer-reviewed work on social media platforms. Censorship regarding novel topics of study is anti-science behavior. Claiming ‘consensus’ in support of public health policies without any scientific analysis of the costs of those policies is recklessly irresponsible and has already cost countless lives.

Claiming ‘consensus’ — without disclaiming all significant sources of uncertainty — is anti-science and violates informed consent to this grand social experiment.

“Instead of championing absolute certitude or objectivity, this research pushes us to ask how scientists and visualization researchers alike might express uncertainty in the data so as to recognize its socially and historically situated nature.

Page 16

In other words, our paper introduces new ways of thinking about “democratizing” data analysis and visualization. Instead of treating increased adoption of data-driven storytelling as an unqualified good, we show that data visualizations are not simply tools that people use to understand the epidemiological events around them. They are a battleground that highlight the contested role of expertise in modern American life.”

Again, they seem somewhat baffled that “orthodox visualizations can be used to promote unorthodox science.” But if us ‘skeptics’ are right, then it makes plenty of sense that we’re able to easily construct so many effect data visualizations. One could apply the same analysis to the ‘consensus’ institutional analysis to understand how and/or why they use ‘orthodox visualizations’ to promote their new scientific paradigm which was inaccurate or not actionable.

I have great respect for anyone who learns and develops complex skills and employs them very explicitly toward the public good or the commons. Even if you’re on “the other side” of a debate, I assume you are also trying to save lives, or at least feed your family. And long ago, I chose to guesstimate that some ~95% of people have great intentions, even if I disagree with their interpretations of the information driving their actions.

But I do also think that groupthink can accomplish an exponential amount of unwitting harm. Gatekeeping ‘the science’ to be curated for a political Overton window must also end, because it already has. Just as they’ve patiently waited to switch to renewables until it’s not a gamble, I’m guessing that the old institutions will eventually participate more with the evolving world of open-source intelligence.

It seems that many people currently support technocracy, consciously or not. Especially this past year, attendees of most science churches have believed many claims without even verifying that those claims are actually published in the publicly available holy texts.

But I do not consent to any further reduction of representation in governance. For decades, I’ve been working to reclaim more representation for we the people. Stronger evidence-based collective decision-making is a great goal. To do so while increasing representation requires catching people up on any relevant scientific topics as they become important. Most humans handle incredibly complex concepts every day. By default, the population must also be treated like rational adults, and we should constantly strive to elevate the national discussion to that of critical thinkers savvy with both data and systems (the work of their government).

If our chronically sick societies want to continue merging medical science with government and politics, then I believe these social experiments would be more ethical on far smaller scales than billions of people. Perhaps next time we run mass experiments with medical interventions, we could find ways to enable communities to ethically opt-in to collect strong data to finally support novel public health policies. Perhaps emergency measures could be voluntarily agreed to before states of emergency are declared. “What do our government prenuptial agreements say about this scenario?”

This concludes my reactions and commentary on the 2021 MIT study. Next, we will discuss my updated conclusions after my rigorous search…

“Akin to, and largely responsible for the sweeping changes in our industrial-military posture, has been the technological revolution during recent decades.

Transcript of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Farewell Address (1961)

In this revolution, research has become central; it also becomes more formalized, complex, and costly. A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the Federal government.

…

The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.

It is the task of statesmanship to mold, to balance, and to integrate these and other forces, new and old, within the principles of our democratic system-ever aiming toward the supreme goals of our free society.”

Crisis In Science: Orthodox Consensus Declared Without Compelling Baseline Evidence

Conclusions After a Search for The “Preponderance of Evidence” for Universal Mask Mandate Efficacy

Check the sources, check the sources’ sources, check the sources’ sources’ sources, and you start getting a sense of how much bedrock exists with the strongest evidence.

I know people are passionate about the science they find fascinating — especially if they are consistently scared to believe specific apocalyptic predictions are highly accurate or certain. Given how many fields and systems intersect for such questions, I empathize with the great scientific challenge of trying to ‘prove’ the claims made by passionate mask advocates. But the burden of proof squarely remains on those supporting extraordinary and universal medical interventions.

Out of all the Nonpharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) widely mandated in 2020, the topics related to masks seem to be among the most studied over the decades. Most community mandate policies cannot be most effectively and ethically studied outside of a state of emergency. If these societal experiments were inevitable, I wish they had been more consensually organized. For example, community-wide medical interventions would have been more ethical if opted into by emergency ballot measures — not governor mandates aided by federal war-time spending.

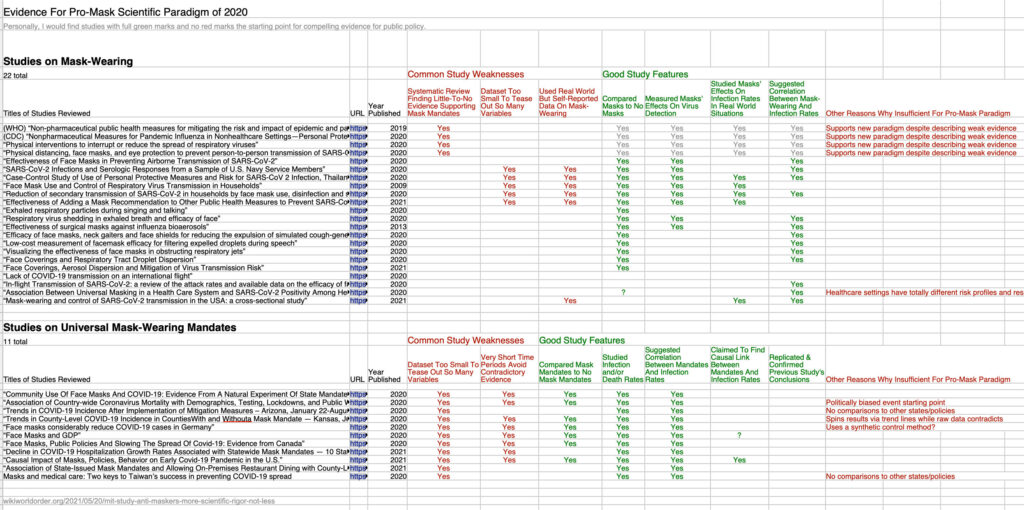

Over the past year, I probably spent a scattered 15 hours trying to understand the evidence behind the 2020 sub-topic of mask mandates. But in Appendix A below, I spent a fresh 20 hours systematically digging through the three references that the MIT study cited for the alleged “preponderance of evidence that masks are crucial to reducing viral transmission.” This portion of my post is perhaps in the vein of a partial, draft literature review.

Below, I’ve copied various quotes from most studies that I personally found most informative or compelling — for or against universal mask mandates. I have not looked for expert critiques of the most compelling studies, and I’ve only shared little objections or nuances which came to my mind’s epistemological virus scanner. But if anyone does find any of these studies to provide compelling evidence for universal mask mandates, they show also search for expert critiques.

I probably misunderstood some aspects of some of these studies because a some of the fields in these studies are less familiar to me. For example, it’s possible I missed a control arm in some studies if was not clearly referenced in the analysis for comparisons with the experimental mask mandates. Any scholars closer to these fields are welcome to improve on and professionalize this starting point. (There is no need for any attribution or credit to this work, but I would love to read any improvements on my work.)

But I think I now have a relatively strong understanding of how much has been published on this sub-topic. I now have far greater knowledge about and what types of questions have been studied, at least all those cited by the ‘pro-mask’ side of this great debate.

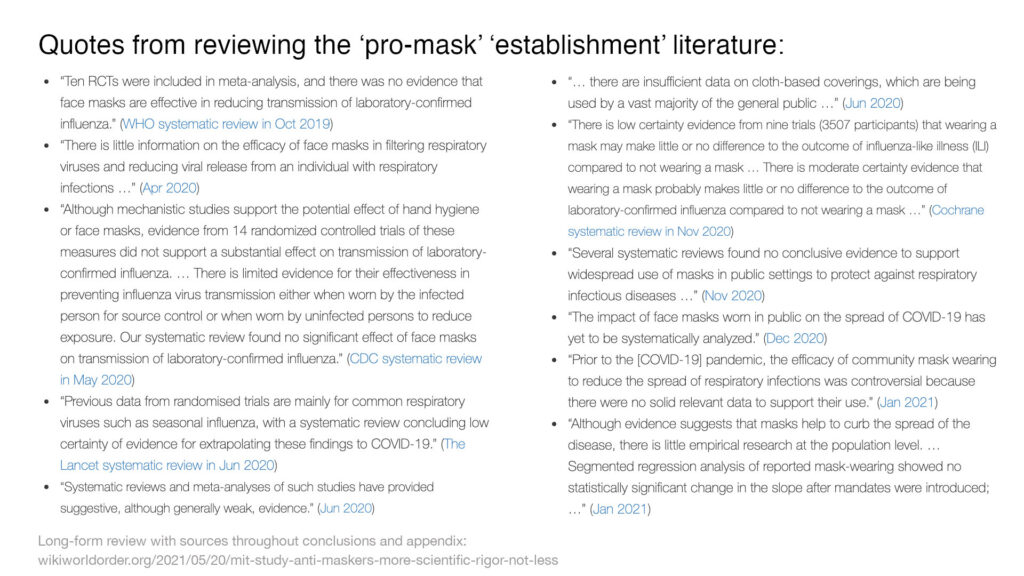

Summary of the “preponderance of evidence” cited to debunk “anti-maskers”:

- Four published systematic reviews concluded that there is limited or no compelling evidence supporting the popular assumption that universal mask mandates are likely to reduce viral transmission. (WHO in Oct 2019, CDC in May 2020, The Lancet in Jun 2020, Cochrane Library in Nov 2020)

- There were a handful of published multivariate analyses which built very interesting models trying to simultaneously tease out many demographic and novel policy variables. Most are less than a year old and claimed to be among the first to show evidence of mask mandate efficacy. In my humble opinion, these are among the strongest pieces of evidence supporting mask mandates, but they are still very far from proving correlation or causation from mask mandates with any actionable certainty.

- A handful of published studies claimed to associate reductions in the rate of change of COVID cases after mask mandates. But only a couple made attempts to show comparisons to any unmasked control arm. And the Kansas study actually showed mask mandate counties to have greater cumulative case numbers overall.

- The only strong new randomized controlled trial on masks (not included in previous systematic reviews) appears to be the Danish study with almost 5,000 participants. But they stated that their “findings were inconclusive.”

- There were probably 1-2 dozen smaller-scale studies emerging in the past year, most involving less than 1,000 participants each, while studying multiple variables simultaneously. Most used self-reported data, and many did not have a control arm without masks.

- Dozens of studies showed compelling evidence that wearing a mask reduces droplets, but likely not aerosols. Only a few of these studies went beyond generalized droplets by testing for potential SARS-CoV-2 transmission and infection reduction.

- Dozens of studies detailed the efficacy of different types of masks, different materials, and/or different layering options. Few went beyond generalized droplets to test for viral transmission and infection.

- Dozens of expert groupthink opinion pieces selectively citing these scattered and weak new studies. They often acknowledge how little is known, but act as if any one of the new studies had the power to overturn the conclusions of the multiple systematic reviews. (If much of this content had been published by Infowars instead of JAMA, then most would consider them conspiratorial musings. If the sudden face mask ‘consensus’ is more conspiracy than incompetence, then these authors may be unwitting or witting accomplices propagating groupthink.)

The most compelling evidence supporting mask mandates has only just begun emerging over the past six months. Until enough is questioned, replicated, validated, etc, the ‘skeptical’ position here should still be considered very rational and backed up by a lack of established evidence for the ‘consensus’.

Quotes from reviewing the ‘pro-mask’ ‘establishment’ literature:

- “Ten RCTs were included in meta-analysis, and there was no evidence that face masks are effective in reducing transmission of laboratory-confirmed influenza.” (WHO systematic review in Oct 2019)

- “There is little information on the efficacy of face masks in filtering respiratory viruses and reducing viral release from an individual with respiratory infections …” (Apr 2020)

- “Although mechanistic studies support the potential effect of hand hygiene or face masks, evidence from 14 randomized controlled trials of these measures did not support a substantial effect on transmission of laboratory-confirmed influenza. … There is limited evidence for their effectiveness in preventing influenza virus transmission either when worn by the infected person for source control or when worn by uninfected persons to reduce exposure. Our systematic review found no significant effect of face masks on transmission of laboratory-confirmed influenza.” (CDC systematic review in May 2020)

- “Previous data from randomised trials are mainly for common respiratory viruses such as seasonal influenza, with a systematic review concluding low certainty of evidence for extrapolating these findings to COVID-19.” (The Lancet systematic review in Jun 2020)

- “Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of such studies have provided suggestive, although generally weak, evidence.” (Jun 2020)

- “… there are insufficient data on cloth-based coverings, which are being used by a vast majority of the general public …” (Jun 2020)

- “There is low certainty evidence from nine trials (3507 participants) that wearing a mask may make little or no difference to the outcome of influenza‐like illness (ILI) compared to not wearing a mask … There is moderate certainty evidence that wearing a mask probably makes little or no difference to the outcome of laboratory‐confirmed influenza compared to not wearing a mask …” (Cochrane systematic review in Nov 2020)

- “Several systematic reviews found no conclusive evidence to support widespread use of masks in public settings to protect against respiratory infectious diseases …” (Nov 2020)

- “The impact of face masks worn in public on the spread of COVID-19 has yet to be systematically analyzed.” (Dec 2020)

- “Prior to the [COVID-19] pandemic, the efficacy of community mask wearing to reduce the spread of respiratory infections was controversial because there were no solid relevant data to support their use.” (Jan 2021)

- “Although evidence suggests that masks help to curb the spread of the disease, there is little empirical research at the population level. … Segmented regression analysis of reported mask-wearing showed no statistically significant change in the slope after mandates were introduced; …” (Jan 2021)

If anything, this “preponderance of evidence” confirms that there is very limited evidence “that masks are crucial to reducing viral transmission.” To me, far more progress must be made on topics like this before high certainty becomes actionable for public policy.

The entire framing of the study is within an assumption that anti-maskers are wrong to question this new scientific consensus or orthodoxy. But reading through the citations for that assumption suggests the exact opposite. So I would be curious to know how deeply the MIT team questioned their core premises while designing this experiment.

After reading the appendix below, if anyone still believes that I’ve missed some overwhelming pro-mask evidence here, then I would be curious to understand what it is, and why you find it compelling enough to establish a new public health paradigm.

I am not highlighting uncertainty within the body of literature. The conclusions of the body of literature are more uncertain than not.

Last year, a scientific ‘consensus’ was declared in support of universal mask-wearing. What compelling evidence overpowered four systematic reviews since Oct 2019 that found little to no evidence supporting infection reduction?

Appendix A: Search For The “Preponderance Of Evidence That Masks Are Crucial”

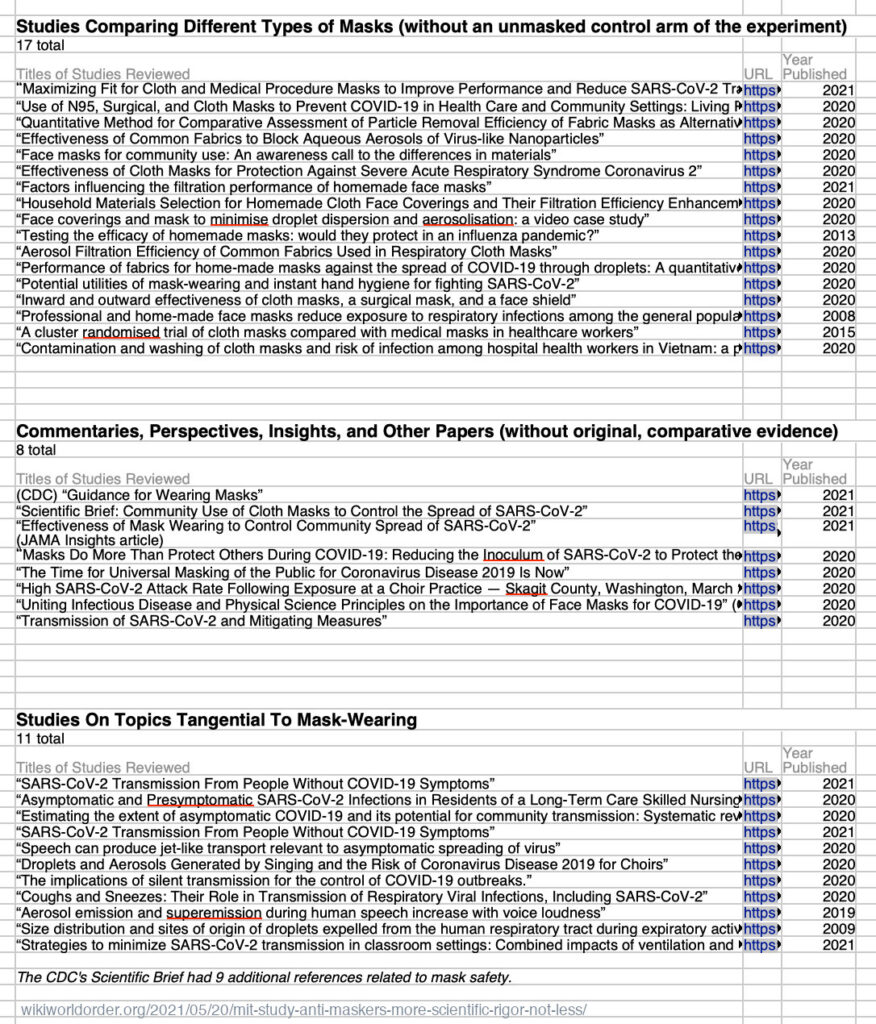

Further below in Appendix B are a few rough attempts to visualize summaries of the 80 studies I reviewed that were directly downstream of the 2021 MIT study’s citations.

Quotes & Notes From My Search For Evidence

Before starting this search I had already read the WHO and CDC systematic reviews. This biased my baselines while looking for studies which are strong enough to start making an evidence-based case for universal mask mandates.

Emphasis within study quotes is added as if highlighting my favorite spots.

“However, despite a preponderance of evidence that masks are crucial to reducing viral transmission [25, 29, 104], protestors across the United States have argued for local governments to overturn their mask mandates and begin reopening schools and businesses.”

Page 1

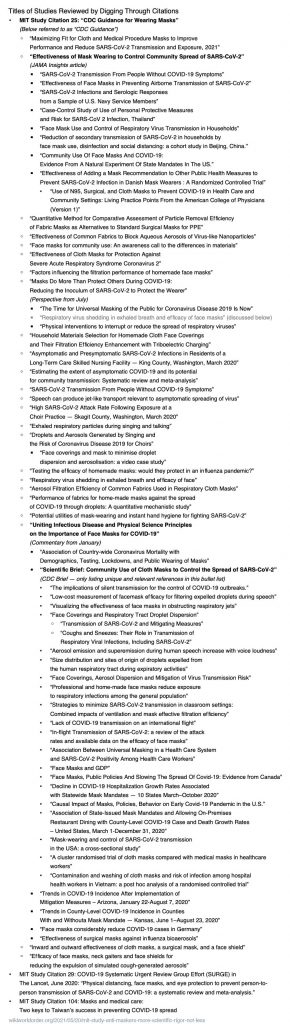

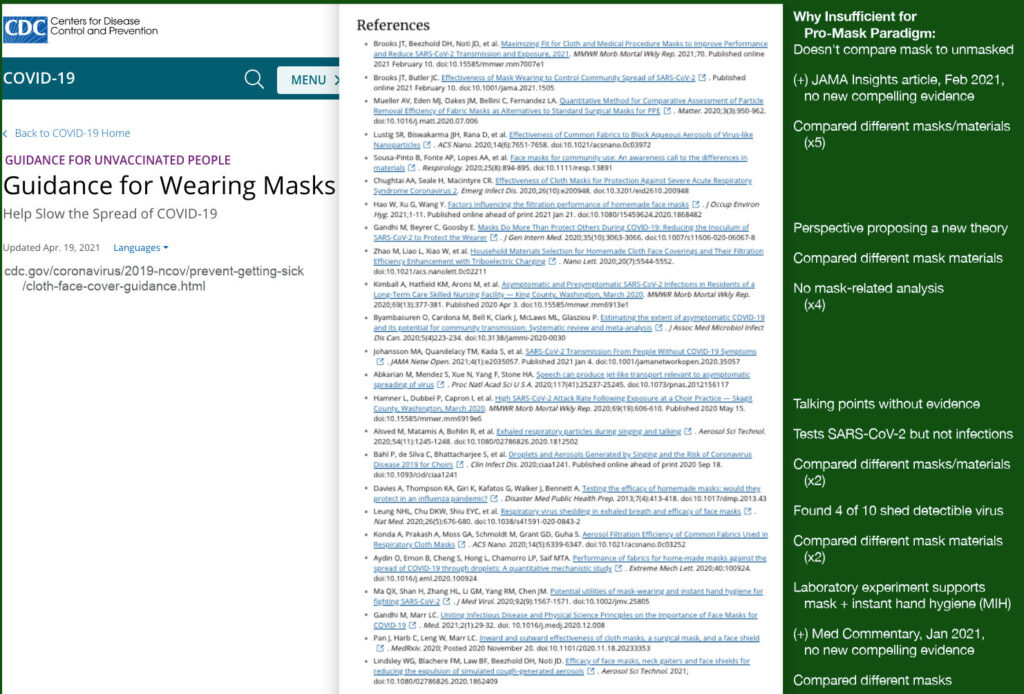

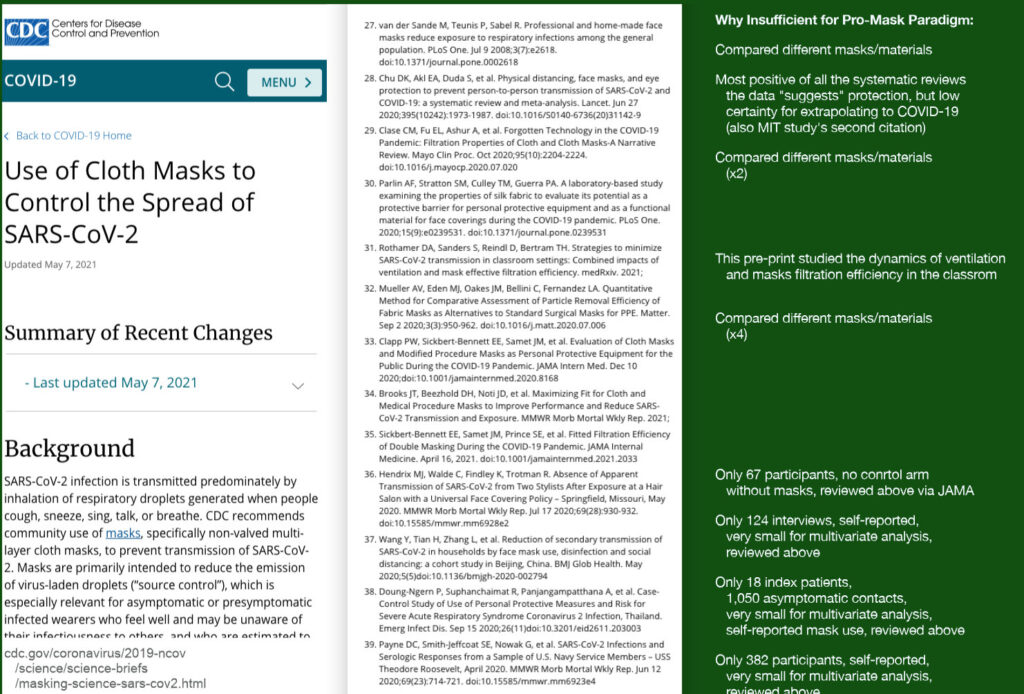

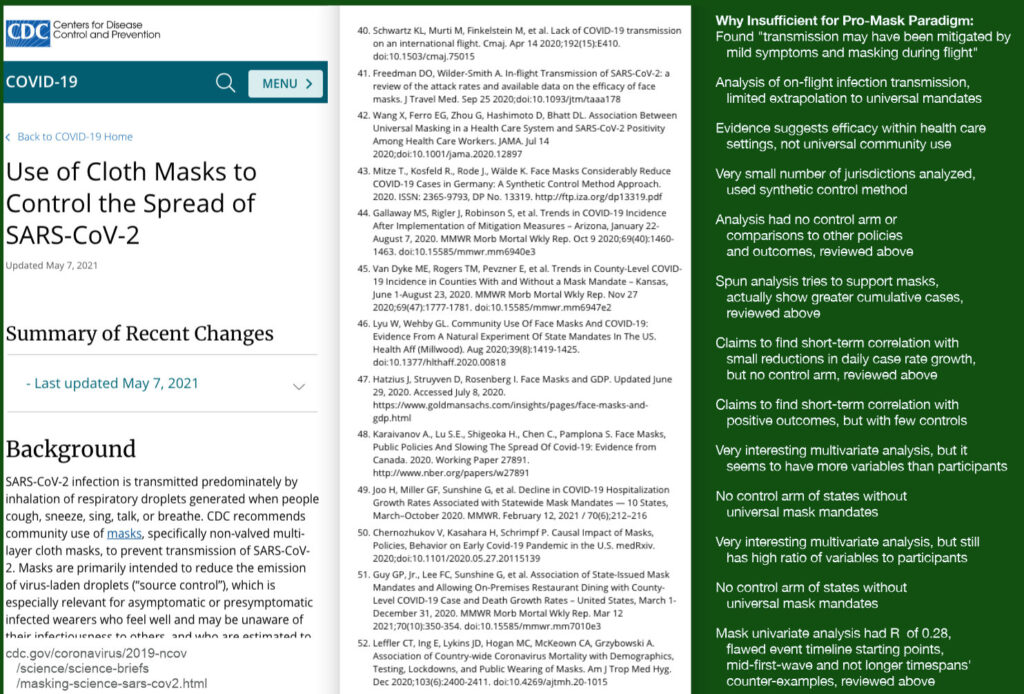

25. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover-guidance.html (5/21 archive)

29. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673620311429

104. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)31142-9/fulltext

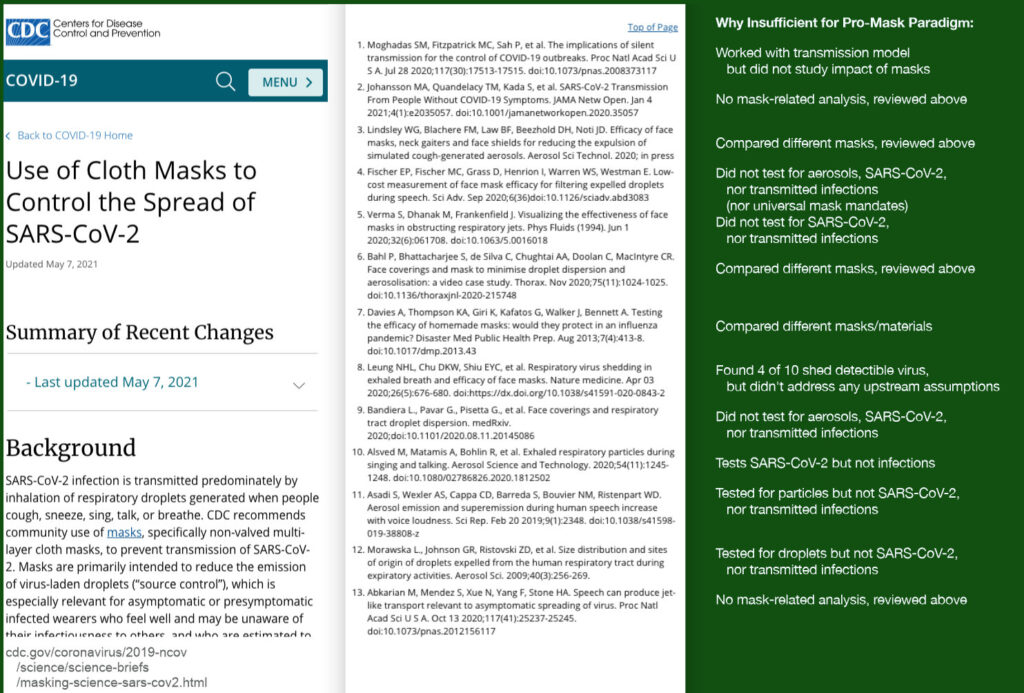

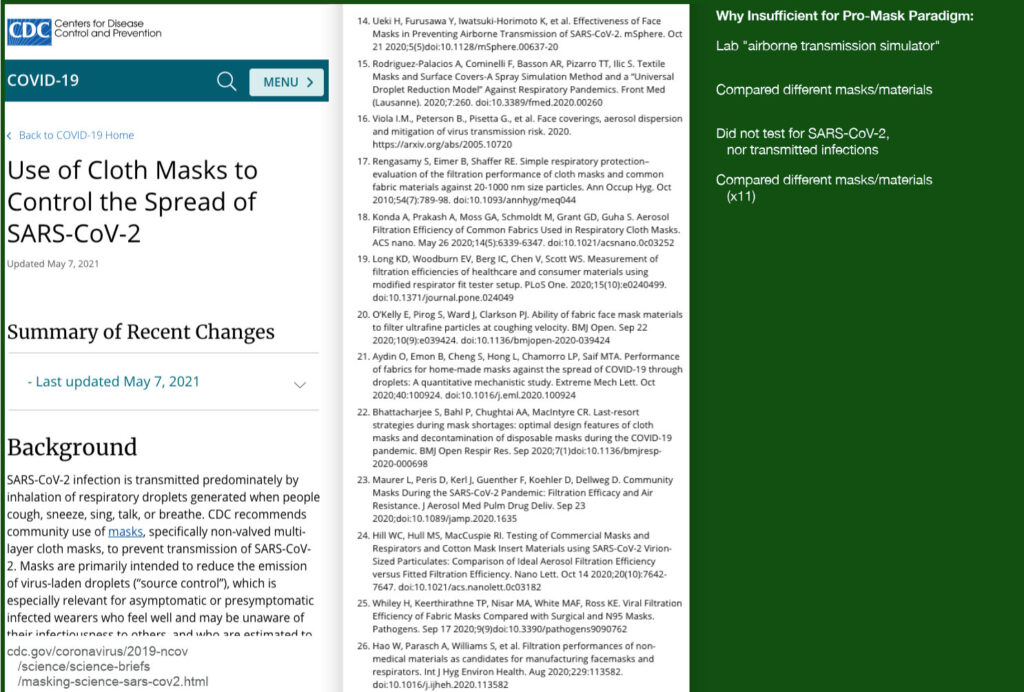

MIT Study Citation 25: CDC Guidance for Wearing Masks

Going through this CDC Guidance page’s 24 references, one by one…

Brooks JT, Beezhold DH, Noti JD, et al. Maximizing Fit for Cloth and Medical Procedure Masks to Improve Performance and Reduce SARS-CoV-2 Transmission and Exposure, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70. Published online 2021 February 10. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7007e1

The above study did not compare mask use to non mask use, and did not explore the impact on viral transmission.

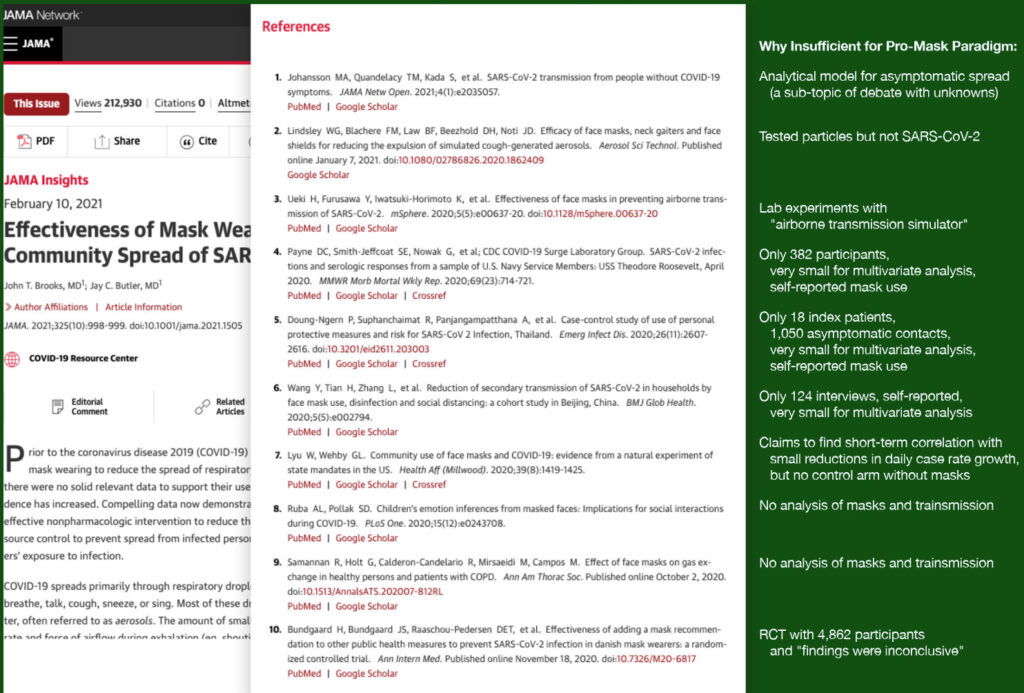

JAMA Insights Article, Feb 2021

Brooks JT, Butler JC. Effectiveness of Mask Wearing to Control Community Spread of SARS-CoV-2. Published online 2021 February 10. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.1505

The above JAMA Insights article from February 2021 says:

“Prior to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the efficacy of community mask wearing to reduce the spread of respiratory infections was controversial because there were no solid relevant data to support their use. During the pandemic, the scientific evidence has increased. Compelling data now demonstrate that community mask wearing is an effective nonpharmacologic intervention to reduce the spread of this infection, especially as source control to prevent spread from infected persons, but also as protection to reduce wearers’ exposure to infection.

…

This aspect of mask wearing is especially important because it is estimated that at least 50% or more of transmissions are from persons who never develop symptoms or those who are in the presymptomatic phase of COVID-19 illness.1”

The above citation in the JAMA Insights article refers to an original investigation from Jan 2021 based on a decision analytical model, “SARS-CoV-2 Transmission From People Without COVID-19 Symptoms”.

“However, the observed effectiveness of cloth masks to protect the wearer is lower than their effectiveness for source control,3 and the filtration capacity of cloth masks can be highly dependent on design, fit, and materials used.”

The above JAMA citation refers to an observational study, “Effectiveness of Face Masks in Preventing Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2,” from October 2020 that “developed an airborne transmission simulator” which looks quite cool, and effective for testing some aspects of mask use, but is far from real-world situations. A few other significant real-world factors include touching, reusing, and unsanitary temporary storage of masks (i.e. resting masks on public surfaces, back pockets, or rear-view mirrors).

These JAMA insights go on to mention and summarize many studies. The first involved 67 salon customers who all wore masks, with no control arm. The second is from Jun 2020, “SARS-CoV-2 Infections and Serologic Responses from a Sample of U.S. Navy Service Members,” studying 382 US Navy service members based on self-reported mask wearing, and a number of other variables were studied:

“Service members who reported taking preventive measures had a lower infection rate than did those who did not report taking these measures (e.g., wearing a face covering, 55.8% versus 80.8%; avoiding common areas, 53.8% versus 67.5%; and observing social distancing, 54.7% versus 70.0%, respectively).”

Next from the JAMA Insights article is from November 2020, “Case-Control Study of Use of Personal Protective Measures and Risk for SARS-CoV 2 Infection, Thailand.” This studied 839 close contacts of 211 index cases, based on self-reported mask wearing:

“We found the type of mask worn was not independently associated with infection and that contacts who always wore masks were more likely to practice social distancing. … Several systematic reviews found no conclusive evidence to support widespread use of masks in public settings to protect against respiratory infectious diseases, such as influenza and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (4–6). … We created 10 imputed datasets and the imputation model included the case-control indicator and variables used in the multivariable models, including sex, age group, contact place, shortest distance of contact, duration of contact at <1 m, sharing dishes or cups, sharing cigarettes, handwashing, mask-wearing, and compliance with mask-wearing.

…

The effectiveness of mask-wearing we observed is consistent with previous studies, including a randomized-controlled trial showing that consistent face mask use reduced risk for influenza-like illness (28), …”

That last line cites “Face Mask Use and Control of Respiratory Virus Transmission in Households” from 2009. That cited study ends its abstract with, “Adherence to mask use was associated with a significantly reduced risk of ILI-associated infection. We concluded that household use of masks is associated with low adherence and is ineffective in controlling seasonal ILI. If adherence were greater, mask use might reduce transmission during a severe influenza pandemic.”

Here are some of the Thai study’s results:

“… handwashing often (aOR 0.33; 95% CI 0.13–0.87); and wearing a mask

all the time during contact with a COVID-19 patient (aOR 0.23; 95% CI 0.09–0.60) (Table 1). Wearing masks sometimes during contact with a COVID-19 patient was not statistically significantly associated with lower risk for infection (aOR 0.87; 95% CI 0.41–1.84). Sharing cigarettes with other persons was associated with higher risk for infection (aOR 3.47; 95% CI 1.09–11.02). Compliance with mask-wearing during contact with a COVID-19 patient was strongly associated with lower risk for infection in the multivariable model.”

This is one of the very interesting multivariate analyses which claim to find a correlation between mask use and reduced risk of infection. But is only based on 18 index patients and 1,050 asymptomatic contacts, while trying to tease out countless uncontrolled variables.

“The first part included demographic and clinical information of the primary case. The second part was mainly focused on the primary case’s knowledge about and attitudes toward COVID-19, and their self-reported practices (mask wearing, social distancing, living arrangements) and activities in the home. The third part was about self-reported behaviours of all family members, as well as the family’s accommodation and household hygiene practices from 4 days before the illness onset to the day the primary case was isolated, including room ventilation, room cleaning and disinfection.

…

This study is the first to confirm the effectiveness of mask use prior to symptom onset by family members, daily household disinfection and social distancing in the home.

…

Our study has limitations. Telephone interview has inherent limitations, including recall bias. It would take about 20 min to complete an interview, and 95% (118/124) of interviews were rated as informative by the interviewers.

…

Household transmission in the pre-symptomatic or early symptomatic period of COVID-19 is a driver of epidemic growth and any measure aimed at reducing this can flatten the curve.

…

This is the first study to show the effectiveness of precautionary mask use, social distancing and regular disinfection in the household, and can inform guidelines for prevention of household transmission.”

The three studies above all use self-reported data and tried to gain insights on at least three different NPIs simultaneously. Given how many uncontrolled variables are involved, these studies are interesting, but do not seem nearly large enough to contain life-or-death-actionable-knowledge.

The next citation in the JAMA Insights article is a study from June looking at state mask policies, “Community Use Of Face Masks And COVID-19: Evidence From A Natural Experiment Of State Mandates In The US.” It says:

“Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of such studies have provided suggestive, although generally weak, evidence.6 The estimates from the meta-analyses based on randomized controlled trials suggest declines in transmission risk for influenza or influenza-like illnesses to mask wearers, although estimates are mostly statistically insignificant possibly because of small sample sizes or design limitations, especially those related to assessing compliance.7–9. There is also a relationship between increased adherence to mask use, specifically, and effectiveness of reducing transmission to mask wearers: In one randomized study of influenza transmission in infected households in Australia, transmission risk for mask wearers was lower with greater adherence.10 Further, the evidence is mixed from randomized studies on types of masks and risk for influenza-like illness transmission to mask wearers; for example, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis comparing N-95 respirators versus surgical masks found a statistically insignificant decline in influenza risk with N-95 respirators.11“

This study of the states from June is among the most productive and compelling I’ve read so far. They claim to have observed mask mandates correlated with a roughly 2% reduction over three weeks in the county-level daily case rate (not cases, nor deaths).

“The study provides evidence that US states mandating the use of face masks in public had a greater decline in daily COVID-19 growth rates after issuing these mandates compared with states that did not issue mandates.”

I didn’t see this accounted for, but I believe many southern states were entering their first wave during this study’s timeframe, while many northern and/or coastal states exited their first wave’s plateau. This study does not have a full control without any masks.

But to better understand their claims in a back-of-the-envelope thought experiment, let’s pretend cases were on the rise at levels which might warrant declaring a state of emergency. Given the reported minimal effect of face masks it’s most reasonable to support masking to “slow the spread” while transmission rates are highest. So let’s imagine cases are doubling every 7 days. Week 0 exists as a starting point of reference with 100 cases. It grows each week to 1,600 cases in Week 4. This simulated control has a cumulative total of 3,000 cases over four weeks (200+400+800+1,600). With a second simulated arm with a mask mandate, we could generously apply a 2% rate reduction starting on Week 1. That means there would be 196% increase each successive week instead of 200%. So in the masked arm, Week 1 has 196 cases, Week 2 has 384, Week 3 has 753, Week 4 has 1,476… for a cumulative total of 2,809 cases, or an overall reduction of 6.4%.

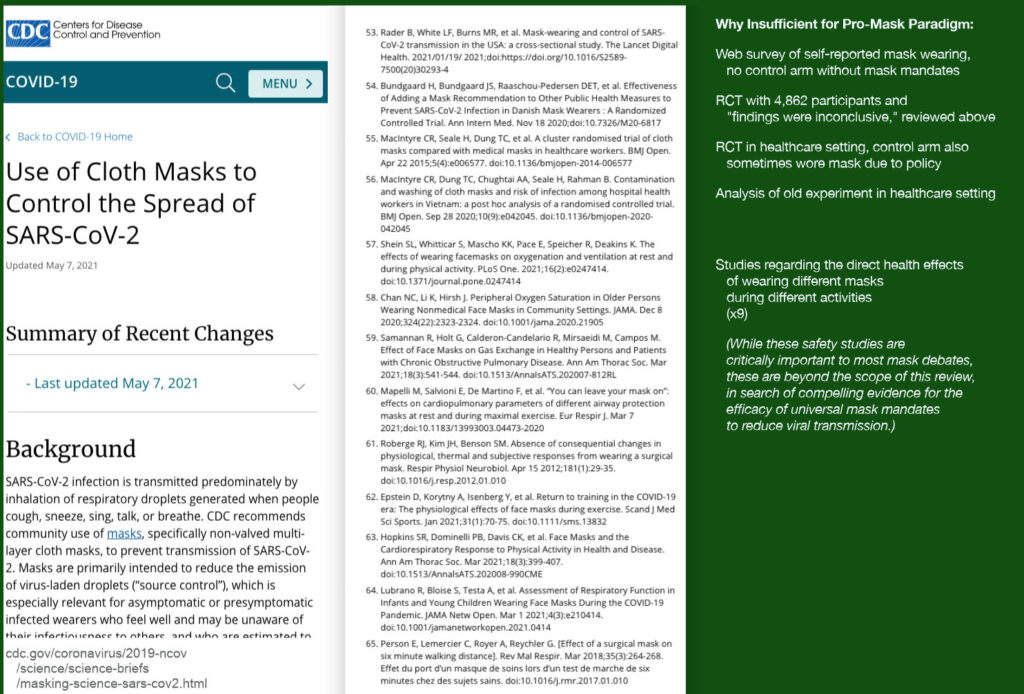

Finally, this JAMA Insights article cites a Danish study from March 2021, “Effectiveness of Adding a Mask Recommendation to Other Public Health Measures to Prevent SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Danish Mask Wearers : A Randomized Controlled Trial.” The JAMA authors say:

“This randomized trial in Denmark was designed to detect at least a 50% reduction in risk for persons wearing surgical masks. Findings inconclusive,10 most likely because the actual reduction in exposure these masks provided for the wearer was lower. More importantly, the study was far too small (ie, enrolled about 0.1% of the population) to assess the community benefit achieved when wearer protection is combined with reduced source transmission from mask wearers to others.”

(The Danish study mentions the CDC’s May systematic review and another one by the American College of Physicians, “Use of N95, Surgical, and Cloth Masks to Prevent COVID-19 in Health Care and Community Settings: Living Practice Points From the American College of Physicians (Version 1).” That strays into the weeds of comparing different types of masks, but might be interesting for many curious minds.)

The January 2021 JAMA Insights article, after presenting a pile of very weak new evidence, concludes by saying:

“With the emergence of more transmissible SARS-CoV-2 variants, it is even more important to adopt widespread mask wearing as well as to redouble efforts with use of all other nonpharmaceutical prevention measures until effective levels of vaccination are achieved nationally.”

But it seems the authors found the Danish randomized controlled trial to be too small, with 4,862 completing the study. That was at least ten times larger than any of previously cited studies used to support their insights. So I am still unclear how the handful of weak studies cited here can overpower the conclusions of four systematic reviews.

The JAMA insights article also has a correction:

“This article was corrected on February 22, 2021, to correct a typo indicating that there were solid relevant data to support community mask wearing to reduce the spread of respiratory infections before the pandemic. This typo has been corrected.”

After making it through the JAMA Insights article, we finally move to citation 3 on the CDC Guidance page…

Back in CDC Mask Guidance References…

Mueller AV, Eden MJ, Oakes JM, Bellini C, Fernandez LA. Quantitative Method for Comparative Assessment of Particle Removal Efficiency of Fabric Masks as Alternatives to Standard Surgical Masks for PPE. Matter. 2020;3(3):950-962. doi:10.1016/j.matt.2020.07.006

Lustig SR, Biswakarma JJH, Rana D, et al. Effectiveness of Common Fabrics to Block Aqueous Aerosols of Virus-like Nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2020;14(6):7651-7658. doi:10.1021/acsnano.0c03972

Sousa-Pinto B, Fonte AP, Lopes AA, et al. Face masks for community use: An awareness call to the differences in materials. Respirology. 2020;25(8):894-895. doi:10.1111/resp.13891

Chughtai AA, Seale H, Macintyre CR. Effectiveness of Cloth Masks for Protection Against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(10):e200948. doi:10.3201/eid2610.200948

Hao W, Xu G, Wang Y. Factors influencing the filtration performance of homemade face masks. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2021;1-11. Published online ahead of print 2021 Jan 21. doi:10.1080/15459624.2020.1868482

The above five studies compared different types of masks or mask materials.

Gandhi M, Beyrer C, Goosby E. Masks Do More Than Protect Others During COVID-19: Reducing the Inoculum of SARS-CoV-2 to Protect the Wearer. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3063-3066. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06067-8

The above perspective published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine in July 2020 presents a new theory. It discusses the potential net benefits of increased asymptomatic spread, which actually sounds closer to a strategy for herd immunity that one might have heard in the 2019 paradigm.

“This theory of viral inoculum and mild or asymptomatic disease with SARS-CoV-2 in light of population-level masking has received little attention so this is one of the first perspectives to discuss the evidence supporting this theory.

…

Our theory is based on the likelihood of masking reducing the viral inoculum to which the mask-wearer is exposed, leading to higher rates of mild or asymptomatic infection with COVID-19. No prior perspective has specifically focused on this link between population-level facial masking, the viral inoculum, and increasing rates of asymptomatic infection with SARS-CoV-2.”

The above July perspective does cite some modeling studies. It also cites another perspective from April 2020 titled “The Time for Universal Masking of the Public for Coronavirus Disease 2019 Is Now,” which mentions that “the debate on whether SARS-CoV-2 is airborne versus droplet is still raging [2–7].” This known uncertainty should have re-framed the entire mask debate and its uncertainty in a very different light, from the beginning. It also cites publications from previous years which would have been covered by the CDC’s May systemic review.

The above July perspective cites a May 2020 study titled “Respiratory virus shedding in exhaled breath and efficacy of face masks,” but this one will be discussed below.

The above July perspective cites a November 2020 systematic review published by the Cochrane Library titled, “Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses.” It says that “The evidence summarised in this review does not include results from studies from the current COVID‐19 pandemic.” So they reviewed roughly the same material as the CDC efforts published in May:

“We included nine trials (of which eight were cluster‐RCTs) comparing medical/surgical masks versus no masks to prevent the spread of viral respiratory illness (two trials with healthcare workers and seven in the community). There is low certainty evidence from nine trials (3507 participants) that wearing a mask may make little or no difference to the outcome of influenza‐like illness (ILI) compared to not wearing a mask (risk ratio (RR) 0.99, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.82 to 1.18. There is moderate certainty evidence that wearing a mask probably makes little or no difference to the outcome of laboratory‐confirmed influenza compared to not wearing a mask (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.26; 6 trials; 3005 participants). Harms were rarely measured and poorly reported.“

The above July perspective piece says:

“One model showed a correlation between population-level masking and number of COVID-19 cases in various countries, but an even stronger correlation with suppression of COVID-related death rates.9 However, it should be acknowledged that this model could not account for all confounders that led to such low death rates in the regions examined.” (“Universal Masking is Urgent in the COVID-19 Pandemic: SEIR and Agent Based Models, Empirical Validation, Policy Recommendations”)

Zhao M, Liao L, Xiao W, et al. Household Materials Selection for Homemade Cloth Face Coverings and Their Filtration Efficiency Enhancement with Triboelectric Charging. Nano Lett. 2020;20(7):5544-5552. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c02211

The above study compares different types of mask materials.

Kimball A, Hatfield KM, Arons M, et al. Asymptomatic and Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infections in Residents of a Long-Term Care Skilled Nursing Facility — King County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(13):377-381. Published 2020 Apr 3. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e1

The above study does not analyze anything related to mask use.

Byambasuren O, Cardona M, Bell K, Clark J, McLaws ML, Glasziou P. Estimating the extent of asymptomatic COVID-19 and its potential for community transmission: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Assoc Med Microbiol Infect Dis Can. 2020;5(4)223-234. doi:10.3138/jammi-2020-0030

The above study does not mention the words “mask” nor “face” but might be interesting for the sub-topic of the risks related “asymptomatic spread” — which has been used to label entire populations guilty before proven innocent.

Johansson MA, Quandelacy TM, Kada S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Transmission From People Without COVID-19 Symptoms. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2035057. Published 2021 Jan 4. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35057

The above study does not study the impact of mask use, but:

“This decision analytical model assessed the relative amount of transmission from presymptomatic, never symptomatic, and symptomatic individuals across a range of scenarios in which the proportion of transmission from people who never develop symptoms (ie, remain asymptomatic) and the infectious period were varied according to published best estimates.

…

Under a range of assumptions of presymptomatic transmission and transmission from individuals with infection who never develop symptoms, the model presented here estimated that more than half of transmission comes from asymptomatic individuals.”

Abkarian M, Mendez S, Xue N, Yang F, Stone HA. Speech can produce jet-like transport relevant to asymptomatic spreading of virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(41):25237-25245. doi:10.1073/pnas.2012156117

The above reference did not study the impact of mask use, but:

“We use experiments and simulations to quantify how exhaled air is transported in speech. … Wearing a mask (as recommended as a mitigation strategy for COVID-19) should be expected to produce more symmetric flow patterns during exhalation and inhalation, localizing airflow around the face.”

Hamner L, Dubbel P, Capron I, et al. High SARS-CoV-2 Attack Rate Following Exposure at a Choir Practice — Skagit County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(19):606-610. Published 2020 May 15. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6919e6

The above study repeats mask recommendations and talking points without discussing any evidence.

Alsved M, Matamis A, Bohlin R, et al. Exhaled respiratory particles during singing and talking. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2020;54(11):1245-1248. doi:10.1080/02786826.2020.1812502

The above study does provide some evidence of potential mask efficacy in a controlled setting, without testing actual infections.

“The aim of this study was to investigate aerosol and droplet emissions during singing, as compared to talking and breathing. We also examined the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the air from breathing, talking and singing, and the efficacy of face masks to reduce emissions. In this study we defined aerosol particles as having a dry size in the range 0.5–10 µm. Although debatable from an aerosol physics point of view, a cutoff diameter between 5 and 10 µm is normally used in medicine for classification of aerosol versus droplet route of transmission.

…

Wearing an ordinary surgical face mask reduced the amount of measured exhaled aerosol particles and droplets to levels comparable with normal talking. However, as surgical masks have a loose fit, some particles may have exited on the sides where we did not measure.”

Bahl P, de Silva C, Bhattacharjee S, et al. Droplets and Aerosols Generated by Singing and the Risk of Coronavirus Disease 2019 for Choirs. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa1241. Published online ahead of print 2020 Sep 18. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1241

The above reference did not study the impact of masks, but cites a 2020 study, “Face coverings and mask to minimise droplet dispersion and aerosolisation: a video case study,” which evaluated the “effectiveness of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended one- and two-layer cloth face covering against a three-ply surgical mask.”

Davies A, Thompson KA, Giri K, Kafatos G, Walker J, Bennett A. Testing the efficacy of homemade masks: would they protect in an influenza pandemic?. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7(4):413-418. doi:10.1017/dmp.2013.43

The above study compared different types of mask materials.

Leung NHL, Chu DKW, Shiu EYC, et al. Respiratory virus shedding in exhaled breath and efficacy of face masks. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):676-680. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0843-2

“There is little information on the efficacy of face masks in filtering respiratory viruses and reducing viral release from an individual with respiratory infections8, and most research has focused on influenza11,12.

…

Our results indicate that aerosol transmission is a potential mode of transmission for coronaviruses as well as influenza viruses and rhinoviruses. … Our findings indicate that surgical masks can efficaciously reduce the emission of influenza virus particles into the environment in respiratory droplets, but not in aerosols12

…

Among the samples collected without a face mask, we found that the majority of participants with influenza virus and coronavirus infection did not shed detectable virus in respiratory droplets or aerosols, whereas for rhinovirus we detected virus in aerosols in 19 of 34 (56%) participants (compared to 4 of 10 (40%) for coronavirus and 8 of 23 (35%) for influenza). For those who did shed virus in respiratory droplets and aerosols, viral load in both tended to be low (Fig. 1).

…

The major limitation of our study was the large proportion of participants with undetectable viral shedding in exhaled breath for each of the viruses studied. … Another limitation is that we did not confirm the infectivity of coronavirus or rhinovirus detected in exhaled breath.”

Konda A, Prakash A, Moss GA, Schmoldt M, Grant GD, Guha S. Aerosol Filtration Efficiency of Common Fabrics Used in Respiratory Cloth Masks. ACS Nano. 2020;14(5):6339-6347. doi:10.1021/acsnano.0c03252

Aydin O, Emon B, Cheng S, Hong L, Chamorro LP, Saif MTA. Performance of fabrics for home-made masks against the spread of COVID-19 through droplets: A quantitative mechanistic study. Extreme Mech Lett. 2020;40:100924. doi:10.1016/j.eml.2020.100924

The two studies above compared different types of mask materials.

Ma QX, Shan H, Zhang HL, Li GM, Yang RM, Chen JM. Potential utilities of mask-wearing and instant hand hygiene for fighting SARS-CoV-2. J Med Virol. 2020;92(9):1567-1571. doi:10.1002/jmv.25805

The above study is from March 2020 using laboratory simulations instead of real-world conditions during a community mandate. It had no control arm without masks, but:

“With these data, we propose the approach of mask‐wearing plus instant hand hygiene (MIH) to slow the exponential spread of the virus. This MIH approach has been supported by the experiences of seven countries in fighting against COVID‐19. Collectively, a simple approach to slow the exponential spread of SARS‐CoV‐2 was proposed with the support of experiments, literature review, and control experiences.”

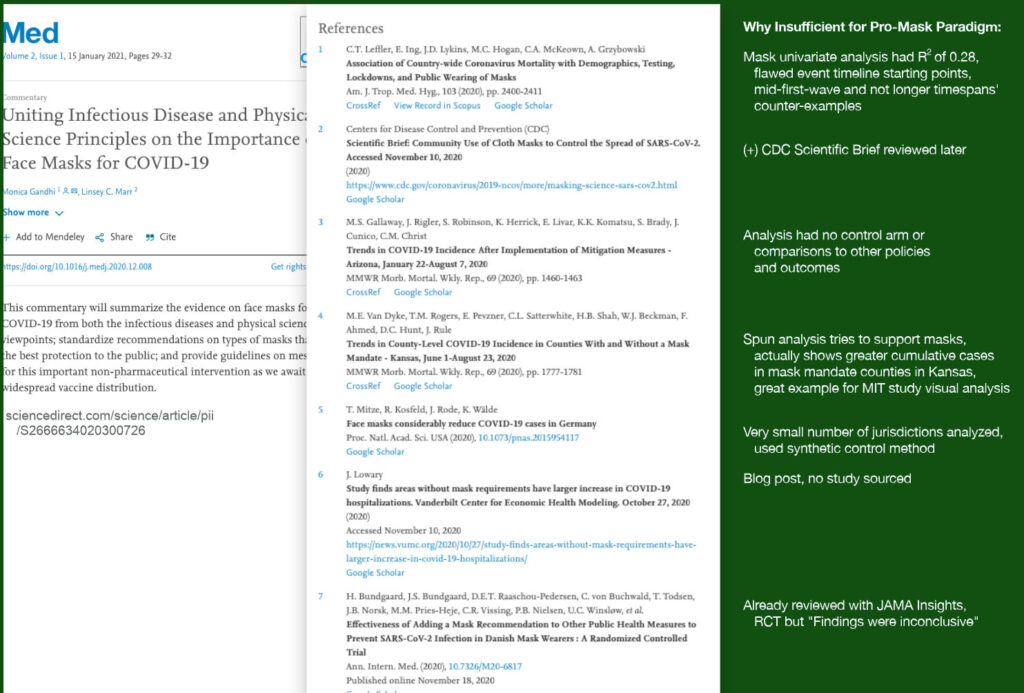

Commentary Published in Med

Gandhi M, Marr LC. Uniting Infectious Disease and Physical Science Principles on the Importance of Face Masks for COVID-19. Med. 2021;2(1):29-32. doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2020.12.008

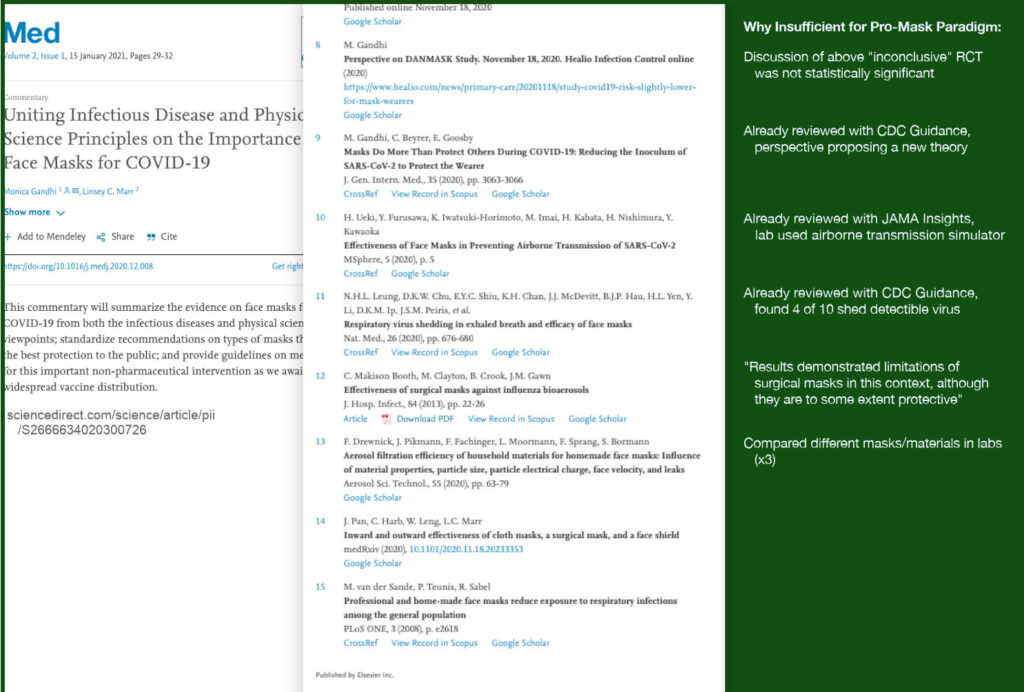

The above commentary from January 2021 was published in Med and summarizes “the evidence on face masks for COVID-19 from both the infectious diseases and physical science viewpoints.”

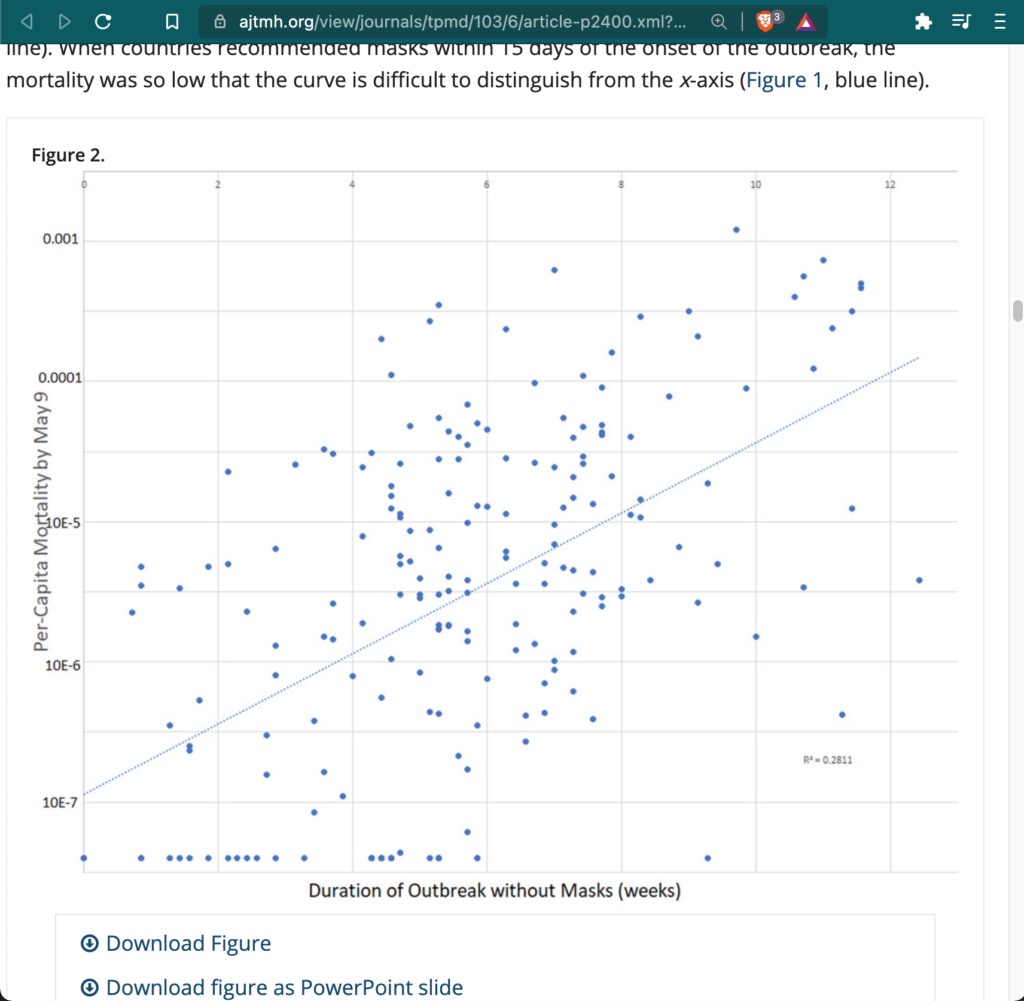

It cites “Association of Country-wide Coronavirus Mortality with Demographics, Testing, Lockdowns, and Public Wearing of Masks” from 2020. This study is more interesting than most:

“To summarize, the duration of the outbreak in the country was defined as the time from the estimated date of first infection (the earlier of 5 days before the first reported case or 23 days before the first death) until April 16.”

Given the variety of case definitions and testing availability, it seems noisy to begin with such an unreliable starting point. For example, instead of starting the outbreak with the first officially/politically defined case, perhaps it would be cleaner to use a proportional threshold like one ‘case’ per million. (For example, the U.S. ‘outbreak’ would have started after our first 330 cases as defined here.)

Looking at Figure 2 with the simple mask analysis, given how many known and unknown variables are also involved, I guess I don’t consider an R2 of 0.28 as actionable enough for life and death decisions for myself or my community. And I would need to see much stronger correlation before believing there was likely significant causation from mask mandates.

“In univariate analysis, scores for school closing, canceling public events, international travel controls, and index of containment and health were significantly associated with lower per-capita mortality (all P < 0.05, Table 3). Policies regarding workplace closing, restrictions on gatherings, closing public transport, stay-at-home requirements, internal movement restrictions, public information campaigns, testing, and contact tracing were not significant predictors of mortality (all P > 0.05, Table 3). Likewise, overall indices of stringency and government response were not associated with mortality (both P > 0.05, Table 3).

A multivariable model in 169 countries found that duration of the infection, duration masks were recommended, prevalence of age at least 60 years, obesity, and international travel restrictions were independently predictive of per-capita mortality (Table 4). The model explained 66.6% of the variation in per-capita mortality. At baseline, each week of the infection in a country without masks was associated with an increase in per-capita mortality of 50.7% (Table 4). By contrast, for each week that masks were worn, the per-capita mortality was associated with a lesser increase of 12.6% each week (given that 1.5072 [0.7471] = 1.126, Table 4).

…

On April 30, 2020, we originally published the finding that the logarithm of per-capita coronavirus mortality is linearly and positively associated with the duration of the outbreak without mask norms or mandates.50 This key finding was recently confirmed using mortality data from June 24, 2020 by Goldman Sachs chief economist Hatzius.73 Their analysis confirmed that, for prediction of both infection prevalence and mortality, the significance of the duration of mask mandates or norms in the model persists after controlling for age of the population, obesity, population density, and testing policy.73 Other work has confirmed that wearing masks during the pandemic can provide substantial economic value.74“

As with the similar studies I’ve read, these are only focused on the first wave. I would be very curious to learn how such multivariable models hold up throughout a whole year. Through this two weeks to slow the year, there seem to have been many strong counter-examples against mask mandates having a significant impact. (Here in Maryland, we’ve been under a constant mask mandates for a year — not just targeting a first-wave spike — without much perceivable legal fluctuation.)

The January commentary cites the CDC’s “Science Brief: Community Use of Cloth Masks to Control the Spread of SARS-CoV-2,” from November 2020. This document has changed since I first read in November, so I will go through this CDC Brief’s updated references after completing the more direct MIT study references.

The January commentary cites “Trends in COVID-19 Incidence After Implementation of Mitigation Measures – Arizona, January 22-August 7, 2020” which does not make comparisons with other policies and outcomes [in other states].

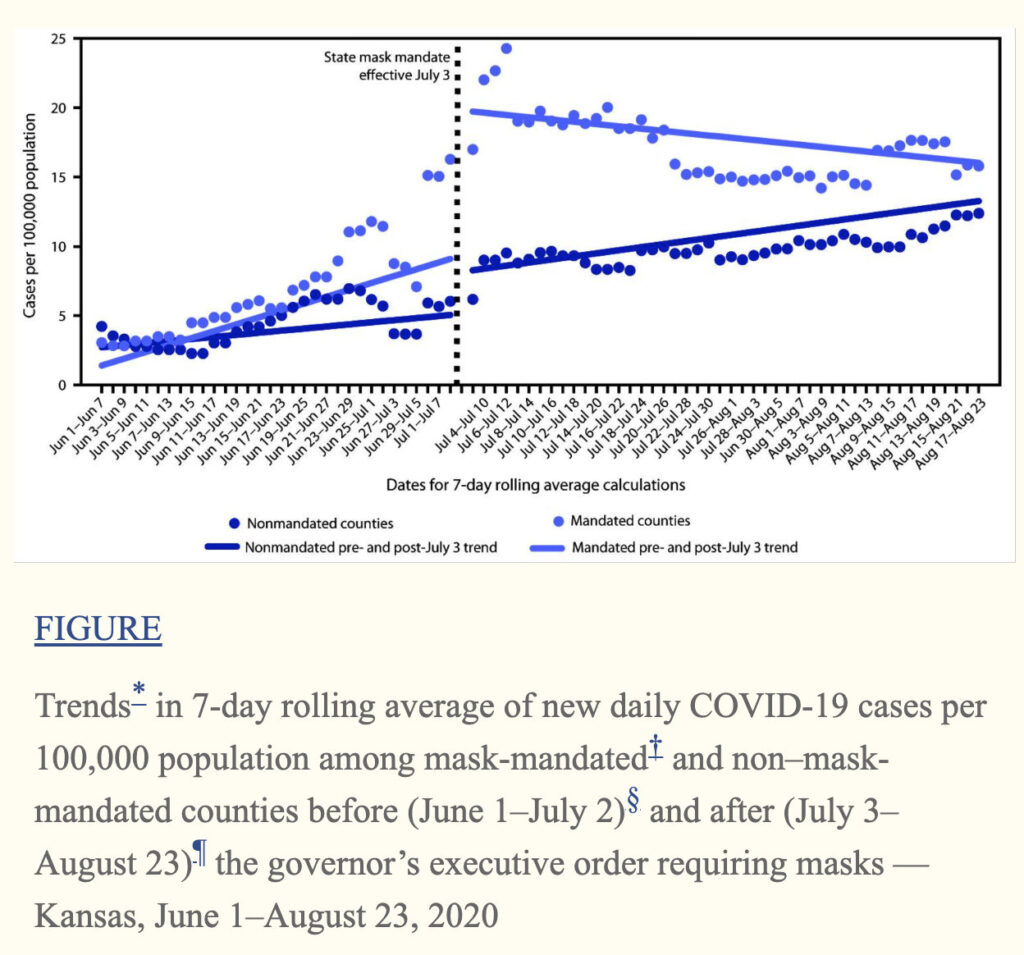

The January commentary cites “Trends in County-Level COVID-19 Incidence in Counties With and Without a Mask Mandate — Kansas, June 1–August 23, 2020.” This study is more interesting, though it does not try to control for many variables. Their trend lines paint an interesting narrative of declining cases for counties after mandates. The MIT study’s words comes to mind… “Researchers have also shown how interpreting data visualizations is a fundamentally social, narrative-driven endeavor.”

It appears the mandated counties collectively spiked surrounding the executive order’s effects — and the nonmandated counties maintained a steady roughly linear rise in case rates. If one measured the total cumulative cases, then the mandated counties would obviously be significantly greater than the nonmandated counties. I also bet that most attempts to apply a single trend line for each arm of the experiment would similarly paint mask mandates in a very poor light. Before controlling other variables, it appears mandated counties has worse net outcomes in Kansas during the selected timespan.

The January commentary cites “Face masks considerably reduce COVID-19 cases in Germany” from December 2020:

“Depending on the region we consider, we find that face masks reduced the number of newly registered [SARC-CoV-2] infections between 15% and 75% over a period of 20 days after their mandatory introduction. Assessing the credibility of the various estimates, we conclude that face masks reduce the daily growth rate of reported infections by around 47%.

…

The impact of face masks worn in public on the spread of COVID-19 has yet to be systematically analyzed. This is the objective of this paper.

…