I wrote another essay in 2016 titled “Please Compartmentalize ‘the Viability of Conspiratorial Beliefs.’” A fan of this essay, Kim, wrote me with some followup questions, which turned into this followup essay. (These essays are cross-posted on Medium and Steemit.)

Part 1: A Reply To Criticism

A criticism of my first essay on this topic has been kindly brought to my attention:

“Lesko assumes that there are only five core conspirators who know how to organize their conspiracy so that a total of 488,275 unwitting accomplices dance to their tune, without even the slightest inkling that they are being instrumentalized by the core conspirators. Lesko thus addresses these core conspirators with a superhuman omnipotence. And anyway: According to his model, every one of the five core conspirators should have such a gigantic social intelligence that he/she can reliably predict and fully rely on that even the 488,275th unwitting accomplice will put his/her conspiracy plans (that of the core conspirator) successfully, reliably, and error-free into practice. Such a model, which subjects the core conspirators to such an almost prophetic gift, is far from reality and not feasible in practice.”

Thank you for these criticisms in this important discussion! I hope you find my responses helpful, and that this clarifies and improves this model.

Defining Success

It seems I should have provided a definition for what I consider to be a successful conspiracy with this model. A successful conspiracy is one where all of the core conspirators’ primary goals/objectives are accomplishing, plus a majority of their secondary goals, without any of the core conspirators getting busted. Accomplishing lower-level goals are bonus perks, but not required. Getting busted means the core conspirator becomes publicly known for their crime and faces some kind of meaning punishment.

We are having these conversations precisely because most successful conspiracies we know about did have at least one fully public whistleblower. That’s not just someone who had an inkling. That’s someone who took tremendous risks to speak out for justice. That’s someone who was usually ignored or smeared by the dominant reality bubbles. Those same reality bubbles have enabled the ongoing success of cover-up conspiracies and ongoing pretense for war conspiracies.

I am often asked, “With so many accomplices, how could they keep the secret?” A more relevant question might be, “With so many whistleblowers, how could the media and government still label these conspiracies as absurdist theories?” How do the conspirators’ cover stories continue to succeed despite those errors? That question could require a few books. Some of these conspiracies continue to succeed only because they go unidentified by the public narratives.

Not only do successful conspiracies frequently survive a couple of whistleblowers, but a couple of lower-level witting accomplices can even go to jail. This is an old strategy in organized crime which gives the prosecution have a win under their belt. As long as all the core conspirators are safe, and the main objectives are accomplished, then it is a success. But they would be trying to avoid having accomplices unexpectedly jailed.

Given so many historical case studies, I do not think most “conspiracy theorists” would ever claim that the success of such conspiracies requires preventing “even the slightest inkling” of unwitting accomplices. If we use that definition or standard, then we have to reclassify the 9/11 Inside Job conspiracy as having failed because there were whistleblowers.

In fact, by this definition of success, we might have only unveiled a few successful conspiracies in all of recorded history… rendering the concept useless. So it would also require us to use more words beyond success and failure to productively communicate about the outcomes of a theoretical conspiracy.

So with all due respect, this is a straw man argument that also moves the goalposts. This argument attempts to redefine a successful conspiracy with an unrealistic standard requiring zero slight inklings from unwitting accomplices. This operational standard itself is “far from reality and not feasible in practice.” If others are using that definition, then please consider this my disclaimer that I do use the concept that way.

The characterization of “superhuman omnipotence” has a similar problem. I did not intend to make that claim. This is not a requirement for other types of organizational leaders in the world of intelligence or business. They evidently meet their goals with a sustainably high percentage of success, and I don’t believe they have superhuman omnipotence. Do you?

Core conspirators are not superhuman. Organizations are superhuman. Core conspirators just have the most access to the organization’s resources and benefits. And large compartmentalized organizations have been historically capable of impressive feats.

I do not claim that successful covert operations always execute cleanly. Their plans are designed to be clean, but real life is not. I study them because they seem to successfully accomplish many of their intended outcomes and because I’m trying to learn from our mistakes of failing to stop them.

I might return some criticisms with questions to those who are skeptical of almost all these theories:

- Why do you think huge operations would require superhuman omnipotence to successfully manage?

- Why do you think conspiracies can only succeed if zero unwitting accomplices see through their cover stories?

- If these turn out to be assumptions without evidence, then where do those assumptions come from?

Manhattan Project Examples

“Years later, when General Groves was preparing his memoir, Now It Can Be Told, he wrote to his son and co-author, Richard Groves, that secrecy in the Manhattan Project had eight objectives:

- “To keep knowledge from the Germans and, to a lesser degree, from the Japanese.

- To keep knowledge from the Russians.

- To keep as much knowledge as possible from all other nations, so that the U.S. position after the war would be as strong as possible.

- To keep knowledge from those who would interfere directly or in directly with the progress of the work, such as Congress and various executive branch offices.

- To limit discussion of the use of the bomb to a small group of officials.

- To achieve military surprise when the bomb was used and thus gain the psychological effect.

- To operate the program on a need-to-know basis by the use of compartmentalization.”

The fourth, fifth and eighth items on this list suggested the benefits to Groves of the intense compartmentation and secrecy he implemented: not only to protect national security, but also to protect his own power and influence from people who might “interfere” – such as the elected representatives of the American public. The reality of bureaucratic interest in secrecy – recognized a century ago by the sociologist Max Weber, who described secrecy and regulation as the core behaviors of bureaucracies – should serve as a caution against accepting every government claim of national interest. Yet the early Cold War set a pattern of doing just that.”

The Manhattan Project was completed with 130,000 people and $2 billion (or $23B in 2018). For the sake of argument, let’s guess that 80% of those accomplices did not know they were building weapons that, 1) would be unnecessarily used at the end of the war, and 2) would then take the world hostage through the present day. That guess implies 104,000 unwitting accomplices. So if that really happened, then I don’t understand what makes 400-500,000 participants inconceivable, especially given communication advances since the 1940s.

Most scientists would know they were doing classified science related to national security. Some would know they were building offensive weapons. Far fewer would understand that — simultaneous with the birth of the modern U.S. intelligence community — they were building weapons that would take the world hostage by the very national security states which co-created them.

Remember… One person’s freedom fighter is another’s terrorist. And one country’s peace project is usually another country’s dangerous conspiracy. Countries often try to thwart the dangerous conspiracies of other countries. Because of this, even compartmentalized peace projects by the “good guys” have similar strategic risks and vulnerabilities for infiltration and leaks as the “bad guys”. This is one of the reasons I think this case study is fair to include as a conspiracy.

If people in the past made different decisions, we could’ve had a different world where the U.S. and U.S.S.R. did not…

- Start building nukes because they thought the enemy would or was

- Steal each others’ notes and thwart each other’s progress

- Complete the nukes because the other would or did

What if the world powers had instead signed a ban treaty as soon as the potential was discovered.

We are not in that different world, and I’m betting that many people lobbied policymakers on both sides to help get us where we are. Most witting accomplices surely thought this would help secure a lasting peace, but I would hope many were also aware of the dangers of this evolution of warfare. Since writing my previous essay, reading National Security and Double Government, by Michael Glennon, has further increased my attraction to treating this cornerstone project as a conspiracy.

The top scientists running the Manhattan Project would have known the conscious goal of creating new weapons so horrible they could overpower the rest of the world. But the core conspirators would have been in a higher tier above them to act on the original concepts, organized early plotters, and secured the funding. These would be deep players in national security, so if they have made public statements about their intentions behind the project, they would be difficult to trust as accurate.

There are countless theories in the 9/11 Truth movement, including MIHOP (“Made it happen on purpose”) and LIHOP (“Let it happen on purpose”). Both of these theories are considered to be conspiracies. Similarly, the Manhattan Project was a MIHOP conspiracy if early plotters likely saw the advantage for the national security state to be able to hold the world hostage, and they went through with it anyway. If the early plotters only had an inkling of the consequences and went through it anyway, then that would still be like a LIHOP conspiracy.

My position has also been characterized as implying that the core conspirators get 488,275 unwitting accomplices to “dance to their tune”.

Projects requiring this much security would function best if all participants were either…

- Vaguely aligned with a subset of The Big Plan’s larger goals, OR

- Have a cover story they can align with, even if it’s based on lies, OR

- Paid mercenaries who don’t ask questions, or wouldn’t even think to ask questions

In this example, most people involved probably thought they were helping a war/peace effort. It wouldn’t be until 1949 that Orwell would science-fictionalize the military doublespeak that war is peace.

A Failure To Define

Many unwitting accomplices may play roles so benign or abstract that they really wouldn’t have “even the slightest inkling”. But it was not my intention to imply that unwitting accomplices always remain unwitting. These compartments would be originally planned to keep specific people or teams in the dark, but also planned with contingencies for any risky areas. As with most operations of all stripes, plans change and they would want to be prepared.

For example, let’s think of an unwitting accomplice who is actually able to connect the dots between their actions and anything nefarious. If they do get the inkling, they might try to figure it out, but from within their team’s reality bubble. In the worst case, we could say they magically uncover the whole conspiracy. But they would still be unlikely to have hard evidence for much that happened outside of their own team.

Witting accomplices would have to start making threats against those people who figured it out. They can try to force them to keep playing along as involuntarily witting accomplices, or keep them silent and off the team. At the beginning of this essay, I have listed several reasons unwitting accomplices might self-censor and methods for threatening them into silence. These threats could be managed by the contingency teams described above.

Another critique doubts that “every one of the five core conspirators should have such a gigantic social intelligence that he/she can reliably predict and fully rely on that even the 488,275th unwitting accomplice will put his/her conspiracy plans (that of the core conspirator) successfully, reliably, and error-free into practice.”

First, well-designed operations include contingencies for many possible scenarios. One of the main reasons for this is precisely because you can’t plan anything to be truly error-free. This yet another completely unrealistic standard to apply to any real-world organization. One of the larger errors conspiracies often have is of course whistleblowers. The fact that all real-world plans are error-prone does not inherently imply that most conspiracies to fail, nor that this fact dissuades core conspirators from organizing in the first place.

Again, if you make “error-free” a required condition for defining successful conspiracies, then very few of them have ever existed. This path once again renders the very concept of a successful conspiracy as imaginary and totally useless. So I will not defend the straw men standing next to my original arguments.

As of 2015, Walmart employs over 2 million people. Given corporate secrecy, companies that large have some degree of compartmentalization and non-disclosure agreements. They surely break laws — and break more laws while trying to change laws. There are currently nine executive managers in corporate leadership.

Can each executive manager “reliably predict and fully rely on” even the lowest member of their department to put his/her plans “successfully” and “reliably” into practice? Yes, in part because employees can get fired for not following orders. This is exactly how most organizations strive to function, and what shareholders demand. So I do not question the plausibility that Walmart has been reliably successful, despite these absurd scales of management. Do you?

This argument also implies that if an organization to achieve such reliable success, then it’s leaders must have “superhuman omnipotence.” I don’t think this is true either. Do you? How much control do you think the top execs have over all their employees?

I do not presume core conspirators or Walmart’s corporate leadership have any “superhuman omnipotence”. But I also do not dispute the fact that massive numbers of people can be effectively controlled within manageable margins of error. It is far from reality to dispute the success of the many organizations that effectively manage over 500,000 employees. It seems self-evident that any conspiracy that large would only be developed by those with the resources and management skills to accomplish it.

The Department of Defense employs 3.2 million people who usually keep different compartmentalized secrets and operations, and many of whom don’t really know what they’re doing. But the existence of the DoD is also not as high an implausible fiction as it should be.

Finally, the closest example of compartmentalization to the models needed for many popular conspiracies would be the CIA itself, with an estimated over 21,000 employees. Using my basic model with teams of five, this fills the first six tiers. I don’t know the best estimates for how many human assets and informants they maintain beyond this to fill the next tiers. And when the CIA ‘wags the dog’, many in the DoD become accomplices including some of the 17,000 with Defense Intelligence Agency, an estimated 40,000 with the NSA, and 3,000 with the Office of Naval Intelligence, plus the 35,000 with the FBI.

Other large and highly compartmentalized organizations include over 262,000 employees in Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSS), 32,000 were in the Nazi’s Gestapo, and more than 6,000 more were in the Nazi’s SS. It does not appear that the Russia FSS has collapsed under all of it’s compartmentalized conspiracies. On the contrary, the mainstream media often seems to think it is one of our greatest threats.

If the CIA grows 5 times larger, will it utterly collapse — or get stronger? What about 20 times larger? Absent compelling evidence, it is arbitrary to assume that compartmentalized conspiracies collapse at some size threshold.

A logical fallacy involved with this common argument is “special pleading” because “there is no adequate reason for treating the situation differently.” Personally, I don’t think it is at all self-evident that the CIA would inherently collapse at larger scales — but would be the hero with a rational organization structure at 20,000 employees protecting deadly secrets.

Part 2: Ways That Unwitting Accomplices Stay Silent

Yes, there are many plausible reasons that “unwitting accomplices” or “helpers against knowledge” might not become whistleblowers. A lot could depend on how an individual’s handler or manager (from the higher tier) frames the situation for them.

One method “core conspirators” could use to plan/design a large covert operation is to determine all the things which need to happen, and all the top-level contingency plans. To keep it light, you could picture a meticulously planned bank heist, magnificently designed so nobody gets hurt. Ideally, unwitting accomplices would not be given access to enough information to know who else was involved — or even figure out that they were involved.

But with the most tragic events, it seems that often the patsies, their handlers, rogue intelligence groups, and funders are accurately defined as terrorists (employing strategies of terror), even if they think they have noble or patriotic motives. Any witting/knowing accomplices who do not perform a suicide mission will have everything to lose if the plan gets busted. So these people are highly motivated to guarantee that all the plans and contingency plans leave a minimal margin for error. They have similar incentives to the core conspirators to carefully design their teams/cells/compartments. A strict rule of careful planning would apply to all witting accomplices at all levels. The ability to perform well would be a prerequisite for anyone recruited to run a sub-project (with one or more teams).

At every level, core responsibilities can be delegated to start gathering information and fleshing out more detailed sub-plans. Some of those sub-plans can be carried out by the next tier — who may or may not be aware that they are involved in something nefarious. The next tier would never be as fully informed as its parent tier (this may be the core definition of “compartmentalization”). An operation that needs to maximize security would want to minimize how many accomplices they use, and this factor would constantly weigh on planning decisions.

But before recruiting any unwitting accomplices, it would be wise to carefully construct a cover story. This is a logical and compelling reality in which they can participate. This reality can be accurate/true but with key information omitted/neglected/withheld, or constructed with fabricated evidence or situations. There would often be a subset of unwitting accomplices who could never guess their involvement until after the conspiracy’s culminating event. The management of that aftermath would need to be built into a plan.

Any witting accomplice can retain plausible deniability if their subordinates’ need to know access to information is well designed in advance. For example, a higher-level witting accomplice could plan the cover story to include explanations for what happened, what “went wrong”, how the unwitting accomplice could not have known any better, or how it wasn’t their fault. They might even be convinced that it’s all just a misunderstanding or unrelated coincidence, and none of them were involved at all.

Unwitting accomplices may or may not be more compelled than the general public to explore and parse the rabbit holes required to figure out what is actually happening. And the mainstream media ignores the strongest evidence for most theories about conspiracies. So most Americans only get to see an occasional straw man argument on the screen.

But unwitting accomplices would still have to overcome their own confirmation bias that conspiracies are rare or impossible. I don’t know what percentage of most Americans have that bias, but the mainstream media claims it all the smart ones — and in my experience, this includes almost all my real-world friends and family. So I presume most unwitting accomplices are less likely to recognize things as suspicious “red flags”. They would be even less likely to search deeper for something they don’t believe can exist — a unicorn hunt.

(I might call them “conspiracy confirmation bias” and “coincidence confirmation bias”.)

That said, those with the opposite confirmation bias (expecting conspiracies to be common) could pose an added security risk to weigh during an operation’s planning process. If needed, such accomplices could be weeded out during the recruiting process, or extra contingencies added to their sub-project.

If they make it past their confirmation bias, then they will next need to overcome far cognitive dissonance. Such epiphanies are like suddenly losing your home. The world view(s) you’ve long grown comfortable in are rapidly washed away, leaving you in a scary foreign place. Humans will often do great mental gymnastics to avoid the mental and emotional pain of cognitive dissonance, even related to far more benign issues than conspiracies.

It would be even more painful to discover you are an unwitting accomplice to some [violent] act you detest. Therefore, some unwitting accomplices would essentially refuse to believe in the conspiracy because it would be too painful a reality. It is a coping mechanism.

It’s hard for most people to get in the mind of a witting accomplice because we don’t like harming or betraying others. And most people think if they were in the shoes of an unwitting accomplice, that they would blow the whistle. But the Asch conformity experiments tried to test “if and how individuals yielded to or defied a majority group and the effect of such influences on beliefs and opinions.” They found that 36.8% “responses conformed to the actors’ (incorrect) answer.” So some people may be more predisposed to go along with a cover story, even if their senses tell them it is fishy.

Some cover stories and sub-projects can be set up specifically to create distractions and sow confusion during the main events. For example, James Corbett’s devastating “9/11 War Games” breaks down how “all around the country, military personnel, first responders and government officials prepare for one of the busiest days of “simulated” terror in history.” Multiple military drills were running for similar events to what was happening in the real-world. In one famous quote, we hear one of the many confused pilots asking, “Is this real-world or exercise?” Using these drill to further compromise of NORAD’s defenses was likely necessary to successfully accomplish the hijacking sub-projects.

After the event, the use of simultaneous drills within their cover story provides more benefits. Such unwitting accomplices can rationally believe that the coincidentally timed errors were because of broader system failure or inadequacies. All they must do is restrict discussions in their own minds, and with their teams, to neglect the aspect that it would be far easier for al-Qaeda to synchronize their attacks with these drills if “they” had at least one witting accomplice inside NORAD. This might even be a hard prerequisite for these sub-projects. Again, cognitive dissonance is waiting for any unwitting accomplices who even start pulling this thread, and that can be enough to prevent the inkling problem from ever starting.

Many accomplices (witting and unwitting) can participate as part of a paid job, not as volunteers. They can be employed by a handler and might risk losing payment for the job, their professional reputation, or even their career. So the operation’s paid employees would an extra set of motives to stay silent.

Finally, if an unwitting accomplice does discover their involvement in a conspiracy, then there are various rationales that might convince them to stay silent. In some political climates, a handler could plausibly argue that it is more important to unify the country after a great tragedy. If they are working for a public institution, then they might fear public distrust of the entire organization because of a rogue faction, still believing the institution’s greater good.

Earlier this decade, Mother Jones published investigations “documenting how the Federal Bureau of Investigation has built a vast network of informants to infiltrate Muslim communities and, in some cases, cultivate phony terrorist plots.” It seems likely that there would have been at least one plot with FBI involvement which unintentionally went forward and killed people. How might an FBI agent handle the aftermath if an informant double-crossed them, or screwed up? How many motivations might they have to help cover-up their involvement?

If an unwitting accomplice does want to blow the whistle, they could risk getting stopped within their institution or by media outlets. Many whistleblowers who have gotten their story to the public had to make multiple attempts, and it is a life-changing decision. For operations overlapping with rogue elements of intelligence agencies, whistleblowers could also face serious blowback from national security laws. Outside of the military, there are non-disclosure agreements.

Those who internally blow the whistle through proper channels risk higher-ups keeping things covered up for the same well-intentioned reasons listed above. If the risks and needs were great enough, it might force the conspirators to design the plan with another accomplice within the organization’s oversight process too. Then the higher-ranked accomplice could reassure the lower-ranked accomplice that they understand the evidence presented and they will take care of it. But the higher-ranked accomplice would be catching that leak specifically to bury it.

Then there are different levels of threats which conspirators can make against witting accomplices — or unwitting accomplices after they discover the conspiracy. This particularly applies to conspiracies that already involve mass-violence. Those conspirators risk losing everything and would be motivated to share their fear as needed. Conspirators can threaten both the individual accomplices — and any families they have — with death, torture, physical violence, ongoing periodic harassment, ruining careers, etc.

The Milgram experiments “measured the willingness of study participants … to obey an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts conflicting with their personal conscience.” “In Milgram’s first set of experiments, 65 percent (26 of 40) of experiment participants administered the experiment’s final massive 450-volt shock.” So most people are willing to harm others in the next room when ordered to by an authority wearing a lab coat. They did not have a gun or any other threats at the disposal of conspirators.

Some jobs in the world often have a strategic preference for people who have no family for whom they might compromise a mission (like suicide missions). But the opposite is also true. Some strategies prefer or require participants who do have a family or at least some other deep vulnerability which can be leveraged as a pressure point.

Other leverage for blackmail could include the evidence of an accomplice’s unrelated crimes, or taboo secrets. Hence, conspiracies with rogue elements from intelligence agencies might have quicker access to impressive blackmail portfolios to silence people.

It’s also worth mentioning that unwitting accomplices also sometimes take the fall for the whole plot as a “lone wolf”. For these patsies, their greatest risk is being killed during the event itself, or before they can testify. Some conspirators also have access to use drugs to mentally neutralized a patsy, removing their ability to defend themselves while wasting in jail. Meanwhile, the conspirators’ public narrative remains intact, and often grows in influence. If the patsy’s voice is heard after their arrest, then the public has already demonized them and few will truly listen.

Some in both the police and media might suspect a conspiracy, but not have enough evidence to prove it. It might be far easier — and beneficial to one’s career — to stick with the lone wolf cover story they were likely spoon fed. Whistleblowers in such a conspiracy would face large resistance to disrupting a nice clean, establishment endorsed, lone wolf narrative where “we got him, so rest easy.” This is another area where institutions usually have a vested interest in protecting themselves from their past errors.

Some witting accomplices would almost always be involved in planning and executing cover-up operations. At the simplest level, it could just be basic situation awareness across the organization. Everyone needs knowledge on every type of relevant evidence they cannot leave behind, and how to manage or mitigate those factors. A bigger cover-up might involve leaving passports in a convenient place at the crime scene. The biggest known cover-ups also require co-opting an independent commission specifically set up to impartially investigate them for high-crimes, treason, etc.

The optimal, unrealistic plan would be to leave zero tangible evidence in existence for their operations. In reality, we usually have a relatively tiny fraction of potential evidence left behind. In other words, conspirators have high success rates for destroying evidence which puts them at risk.

They can additionally leave enough evidence to frame a patsy or their adversary. Framing an adversary for a crime is called a “false flag”, and incorporating it can instantly double the big-picture strategic gain for the conspirators. When the conspiracy’s cover-up includes the false flag strategy, then this further changes the dynamics.

It usually takes just hours or days after a false flag for the media to start discussing the primary suspect(s), and quickly provide a face for the alleged enemy. So any of those unwitting accomplices who have an inkling will now also have to compete with disinformation in the descriptions of a much different conspiracy like the patsy cover story. The patsy presents a clear direction to channel their anger, fear, and desire for revenge. And very quickly, this becomes yet a layer of world view which the unwitting accomplice must mentally push through before they can start guessing the conspiracy, or become a whistleblower.

At the end of the day, the most effective real-world conspiracies are completed, covered up, with primary goals are accomplished, and years of lead time before there’s a significant group of people with evidence to challenge their narrative and truly targeting the conspirators. At that point, in one sense, it is too late.

There is another motive unwitting accomplices have not too talk. “What’s the point if I can’t change anything that happened and no one will even believe me?” Well, I for one want to at least see more justice in the world. And with the silencing and jailing of whistleblowers, a feedback loop will produce fewer and fewer whistleblowers for the “Skeptics” to ignore. Whistleblowers can often expect to face brutal character assassination or “hit pieces”.

The mainstream media sometimes initially covers that a whistleblower exists, and is making claims. Then later, they cover the story from one more angle (in unison) which “debunks” the whistleblower’s claims (usually the weaker claims). It doesn’t matter how accurate the debunking is, because the whole story is dropped for a decade without any rational debate or consistent skepticism for all the evidence at hand. Unwitting accomplices and outside researchers have to deal with this systemic bias in addition to the above factors.

There’s a serious problem with this circular reasoning or begging the question…

There couldn’t be many big conspiracies because you almost never hear from whistleblowers. And you don’t need to take the whistleblowers too seriously, because there are almost never big conspiracies.

When people ask “Why doesn’t anyone talk?”, the question has a faulty premise, because some accomplices do talk. We call them whistleblowers. I ask “Why don’t people listen, and change our collective course?”

Part 3: Examples of Unwitting Accomplices Who Find Out Later

This entire thought experiment includes conspiracy theories that are not recognized as accurate by mainstream reality. One would only consider people involved as unwittingly accomplices if there was indeed a conspiracy, and one saw enough evidence for its theory to prevail.

Throughout this essay, I do not describe these scenarios as formal accusations. I find most of these theories fairly compelling, but near-certainties are rare in my book. I’m just attempting to organize some patterns to help us categorize and deduce what strategies may be most attractive, effective, and likely for conspirators.

Out of the 130,000 people employed on the Manhattan Project, most would not have understood even a general sense of what they were helping build. This world wonder example of compartmentalization has the most patriotic motives aiding its silence. But the reveal came after only four years, and we learned a great deal more within decades. So I presume there are countless interesting stories about the realization process for unwitting accomplices in this chapter of history.

I also haven’t studied the “moon hoax” theories enough yet, and those projects are still more deeply locked down within the national security state. After all, I don’t even have limited certainty regarding what happened at The Pentagon, 15 miles away, 18 years ago, in broad daylight.

JFK’s assassination is another topic which I know is so vast that I have only skimmed the surface. You might be most likely to find someone who spoke out after realizing they were an unwitting participant in the cover-up for that coup. But it seems likely that Lee Harvey Oswald himself was an unwitting participant turned patsy, and he did publicly declare his innocence. Perhaps he began as a witting accomplice in some cover story he was given by his handlers, but then he was framed to look like the president’s lone assassin.

RFK’s assassination was likely a much thinner conspiracy pinned on Sirhan Sirhan, who claims he is innocent, with details which make him a patsy or unwitting accomplice. It appears that the available evidence proves that he is not guilty of murder, and this alternative history should no longer be considered a “theory”.

We now know the Gulf of Tonkin Incident that kicked off the Vietnam War was based on “skewed” intelligence from the National Security Agency (NSA). “Senior officials at the Agency, the Pentagon, and the White House were none the wiser about the gaps in the intelligence.” “President Johnson and Secretary of Defense McNamara treated Agency SIGINT reports as vital evidence of a second attack and used this claim to support retaliatory airstrikes and to buttress the administration’s request for a Congressional resolution that would give the White House freedom of action in Vietnam.” In the 2003 documentary, The Fog of War, McNamara “concedes that it now appears this attack didn’t happen but claims that he and Johnson honestly believed that it did at the time.” This skewed intelligence is not widely recognized as a conspiracy. But from my point of view, he admits to being an unwitting accomplice of starting to cruel war on false pretenses.

After the Waco siege in 1993, a “grand jury, in its five-count indictment against Johnston, alleged that he hid evidence about the FBI’s use of pyrotechnic tear gas during the 51-day standoff between federal agents and Branch Davidians, and lied to federal investigators and grand jurors during the investigation of the standoff, which ended with a fatal fire on April 19, 1993, killing some 80 Davidians.” Perhaps it’s worth searching related reports for any internal whistleblowing by unwitting accomplices involved in the siege or the cover-up.

A whistleblower did take the stand in the McVeigh trial for the OKC Bombing claiming “that the lab where the bombing evidence was examined was contaminated beforehand with explosives residue.” I think it is likely there would have to be some unwitting accomplices in this case related to the cover-up. (I’ve just found another rabbit hole that’s new to me, Cory Snodgres, “CIA Black Ops Whistleblower: The OKC Bombing was the FBI/ATF Destroying Files”.)

There are also many historical cases where massive corporations have conspired to damage the health of the public and/or the environment. Many of them include stories of unwitting accomplices who turn into whistleblowers.

I don’t know of any unwitting accomplice whistleblowers for the 9/11 attacks themselves. There were many unwitting accomplices within the White House, NORAD, the pilots running drills, etc. You should be able to find some accounts in the 9/11 Commission Report documents. There’s one famous close call in Michael Springmann, the former head of the American visa bureau in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. It sounds like if the CIA had been more honest with him, he might have turned into an unwitting accomplice instead of getting fired and blowing the whistle.

Similarly, there must have been unwitting accomplices in the EPA cover-up of the extreme health hazard to first responders, and I don’t know if any have spoken out. But we know this because Cate Jenkins was too tough to be unwitting, and blew the whistle. “Beginning shortly after the attack, and continuing for years afterward, Dr. Jenkins attempted to bring the EPA’s faulty and fraudulent air quality testing practices to the attention of anyone who would listen.”

The two co-chairs of the 9/11 Commission, Thomas Kean, and Lee Hamilton, later said it was set up to fail, so they eventually became witting accomplices of the crime’s cover-up. Max Cleland also came out saying the investigation was compromised. Presuming these three were not knowing members of a cover-up before they joined the commission, then they fit this category.

Colin Powell’s “high-profile February 2003 prewar presentation to the U.N. Security Council included now-discredited claims…” “Powell said he relied on the CIA to help develop his U.N. presentation but that he was not aware at the time that “much of the evidence was wrong”.” FBI Director Robert Mueller also spread this “intelligence”, presumably another unwitting accomplice of starting multiple wars on false pretenses. Intelligence agents and department heads in all 17 agencies who rubber-stamped the “skewed” “intelligence” were accomplices. Members of Congress who approved or funded military engagements were presumably unwitting accomplices, but many organically aligned with the conspirators’ larger goals/objectives. The media also holds significant responsibility, as the conspiracy also requires their complicity to succeed, unwitting or not.

Establishment think tanks prepare white papers to justify and execute wars, making them presumably unwitting accomplices too. Though some might be witting accomplices, like the Project for the New American Century (PNAC) — whose members had great influence at the time — and their famous pre-9/11 roadmap hypothetically mentioned how it would be easier to build their vision after something like a “new Pearl Harbor”. Their hands might not be as dirty, but they often play critical roles in convincing the public to accept and approve of the conspirators’ narratives. And perhaps some think tank employees have been unwitting accomplices by producing intelligence which insiders can actively take advantage of while profiting on foreknowledge of wisely targeted chaos.

And there’s another broad framing outside of any organizational chart. Voters are definitely witting on some levels and unwitting on others. But that doesn’t let them off the hook, because people should not consent to these unaccountable institutions at all if we have no idea what the intelligence agencies really do. Giving voters informed consent seems like it might contradict such agencies’ modus operandi.

But evidently, voters have not sent strong enough messages to end these wars. 62 million people voted to reelect Bush in 2004. So if someone believes that we have representative governance, then they might also consider those U.S. voters accomplices in these wars.

But millions of these unwitting accomplice voters over the years have spoken up and protested after realizing how the conspirators’ skewed intelligence and demands for patriotism (cover stories) had fooled them into endorsing and thereby enabling mass-murder. This set of whistleblowers has no privileged information up its sleeve.

If any of the other major terror events and mass shootings did, in fact, involve patsies, then those would also be unwitting accomplices if they didn’t know they were involved with anything nefarious. Almost all in the known candidates in the past two decades were quickly killed or mentally neutralized.

Part 5: Questions About Tier 1

In this model, Tier 1 consists of a team of five core conspirators, Mr. A through Mrs. E, with full knowledge of “The Big Plan” they are orchestrating. Each of them will directly control or strongly influence five more accomplices/participants in a team. After Tier 1, each accomplice could really be either witting or unwitting, depending on what is needed and/or what is possible.

This might depend on the scale and diversity of the overall operation. For example, some small plots might not have any unwitting participants. Huge operations might need primarily witting accomplices filling the first few tiers, but varying ratios of witting and unwitting accomplices can work lower in the chart.

In this model, Mr. A controls Team 2.A on Tier 2, which has five members including at least one leader, to be held responsible for the team’s objectives. Each Tier 2 member, or their team as a whole, maybe witting or unwitting accomplices. Each of the other four core conspirators in Tier 1 manage similarly structured teams.

In reality, a plot’s organization would not be designed based on some magic team size. It would be influenced far more by the needs and available resources of the operation. Each team’s size would vary on a task-by-task basis, like with most organizations. Maybe two or three accomplices team up to take care of smaller tasks. Maybe other tasks simply cannot be done without 10 or 20 people in one place. Depending on the situational context, the team’s size might inform whether to use witting or unwitting accomplices and how to manage them.

The planning process would also include tough puzzles of how to further compartmentalize tasks until they are small enough to secure, or backed up with enough contingency plans.

In this model, each team/cell/compartment of five accomplices are all aware of each other, at least as much as needed to collaborate on their compartment’s tasks. So the Tier 1 team of core conspirators are all aware of the plot’s big picture, and any critical details they all need to know.

Lower tiers likely include teams of witting accomplices who would be aware of each other, and everything they need to about the team’s sub-plot, but not the bigger picture. Lower tiers likely also include teams with unwitting accomplices, who would ideally have a cover story that plausibly exists outside the context of the entire plot.

The division of labor among the Tier 1 core conspirators (Team 1) would always depend on a case by case basis. Every large organization faces challenges in completing complex projects. Dividing up tasks can be similar to most common business management strategies, where a hierarchy of participants are also expected to generally follow orders and be held accountable.

It seems that Team 1 must first clarify what their primary and secondary objectives are, and generally how they might securely pull it off. Only then would it be worth discussing roughly how to compartmentalize the various sub-projects. Once enough of that information is clear, then they would be more prepared to split up specific tasks, responsibilities, and entire sub-projects. Team 1 presumably delegates most of their deliverables to lower Tiers.

So operations would need to be well managed like any other business. Compartmentalization is just added on top as an additional strategy with its considerations. Maximum compartmentalization is not necessarily ideal to accomplish the mission and keep it secret, so it wouldn’t always overrule common operation designs. But the strategy might be used wherever specific risks exist to create an extra firewall, increase plausible deniability, and ensure that all witting accomplices feel secure and confident in success.

It seems like if it is done right, heavily using a strategy of compartmentalization would significantly increase the planning time in advance of the operations. It would also increase some communication times between the network of teams, checking in with different handlers, etc. For intelligence agencies used to it, this is just part of the delays and costs demanded by tradecraft used in their covert operations.

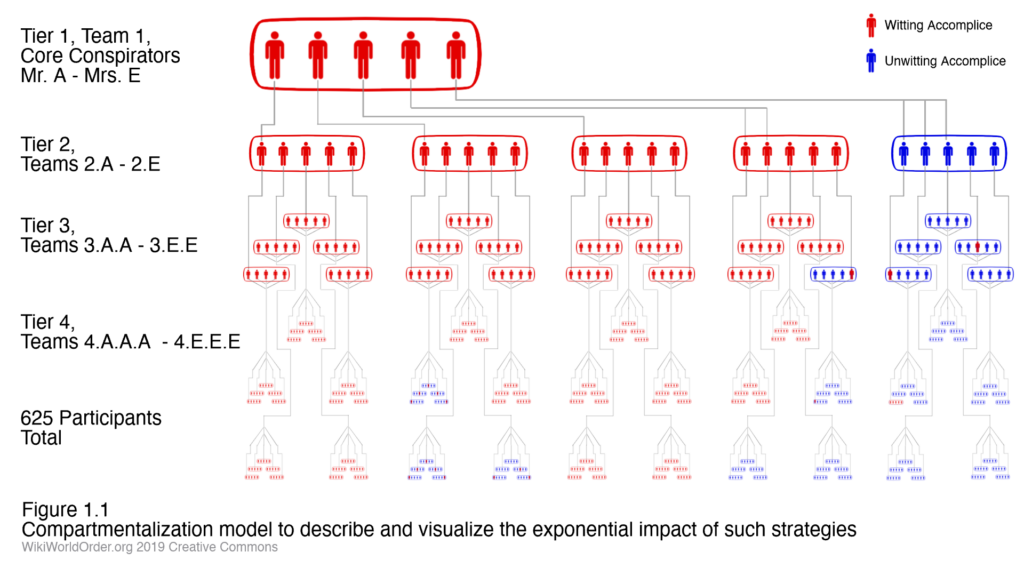

The basic organizing strategies which make sure things get done are shared by both businesses and compartmentalized conspiracies. But in business, everyone in the company — and the world — know the CEO, mission statement, growth plans, stock price, etc. And in the compartmentalized model in Figure 1.1, there are 620 accomplices organized by only five core conspirators who know the whole plan and only five more accomplices who can even identify them.

Part 6: Questions About Tier 2

I do imagine teams throughout the whole network as having one or two leaders. They are ultimately responsible and accountable for their team’s duties to other teams or handlers above and below them. I presume this because hierarchies are very common when people or businesses organize. Similar to other factors above, there are countless ways to design most organizations, so each team should be customized for each specific task.

In Figure 1.1 above, the intent is to show that Mr. A (Core Conspirator A) is managing/controlling one lead member of Team 2.A. This team leader would be in private contact with Mr. A, but the rest of the team would not be aware of Mr. A’s existence.

With this method, Mr. A of Tier 1 privately passes on key information, instructions, and commands to the leader(s) of Team 2.A. The team leader passed on instructions intended for the members of their team and completes any other commands ordered for them alone. If the team leader runs into any issues or successfully completes their tasks, only they would be able to reach out to Mr. A. (But Mr. A can reach out to Team 2.A in a contingency situation.)

Depending on the people and the job, some teams could have a couple of co-leaders. Or the team could have a primary leader who doesn’t realize there is a second/backup leader also being directly steered by the core conspirator above them.

Again there are countless variations possible. In a different plot, using “Variation #1”, Mr. A could be a known member of a few other heavily trusted teams. So instead of relaying instructions to Team 2.A through an intermediary, he might be the known leader of that team. He may be there under his real identity or a cover identity, as needed. But he would still presumably omit or downplay the core conspirators‘ bigger plans from Team 2.A.

I do think this Variation #1 an equally reasonable default model for laying out the entire structure of a hypothetical organization. This strategy definitely removes one layer of protection/firewall for the core conspirators. But it also gives them more direct control over the second tier. So a decision to use this strategy depends on the situation’s security needs, but also the core conspirator’s management style, or some strategic value of their identity (real and/or cover).

In this example, if Mr. A privately manages the leader of Team 2.A, then only five people can identify him. That’s the four other Tier 1 core conspirators, and the Tier 2 team leader. But if Mr. A actively leads the team himself, then 8 people can identify him. Jumping from 5 to 8 here is a 60% increase in direct exposure risk in that spot. So they might need to add extra contingency plans, quality control, and blackmail portfolios to counterbalance the overall risk for The Big Plan.

So once again, there are many design options to fine-tune different aspects of an operation.

But if Mr. A has duplicate roles, we would have to update the model’s math of calculating how many total unique participants are involved. And we could evolve it to become ever more complex, spending months classifying dozens of different general strategies, and making relatively arbitrary guesses to weigh the likelihood of their use in different categorized scenarios.

I think this direction would only take the model further from reality, without producing more statistical value, higher resolution, or actionable results. If my simplified model cannot help convince Skeptics that such organizations are plausible, then I doubt a more convoluted model would tip the scales for them. Because it will always just be a generalized, simplified model of an infinitely complex chaotic system of human relations.

With the catastrophic anthropogenic global warming models, I would prefer if society focused the collective resources towards implementing the applied science we already have, instead of pumping it into theoretic questions that we probably won’t be able to answer this century. It is my position that we would have saved almost two decades of fossil fuel use if the government had simply been buying and installing solar panels for the past three decades, using a majority of the environmental funds that appropriated to research the nested climate change theories.

This strategy preference is a result of my unique blend of bias, but given the evolution of this discussion, perhaps the model has far greater value in establishing consistent definitions for use in discussing specific conspiracies. Such frameworks can be useful to researchers, providing a more standardize layout to describe whatever they uncover. If these concepts become well-defined and accepted by most people, their use could generally improve communications across one of the most prominent and damaging reality-bubble-divides, which catalyzed an entire “alt-media” counterforce.

The most secure way to compartmentalize would be to ensure that most teams do not knowingly interact with each other, or are even aware of each other. Ideally, Team 2.A shouldn’t even know Teams 2.B through 2.E even exist. I think this rule is part of the default modus operandi for compartmentalization, and it is the intended rule for this model.

But Team 2.A would collectively know about the teams it managed, 2.A.A through 2.A.E. Depending on the security needs and divisions of labor, individual members of Team 2.A might be the only ones with full knowledge of a lower team they manage. Or the whole team might need or want to work more transparently to manage their collective responsibilities.

If a plan is highly compartmentalized, then there are likely many situations that would require separate teams to work in parallel — or even together. They can work together by carefully accepting a specific compromise of maximum security, allowing one member from each team to be in contact. Alternatively, a separate team in an entirely different branch of the operation could facilitate communications, creating an extra firewall.

For example, perhaps some of the Tier 3 teams managed by Mr. C are essentially liaison teams. These would be witting participants simply transferring [coded] information between the teams/cells/compartments. Picture the movies where the CIA agent calls some funny number, speaks some code phrases, and an intended message is passed to their handlers. The call center agent receiving the field agent’s call does not need any context about any operations to accurately and securely move the information through the fully compartmentalized organization.

The CIA does not have a monopoly on tradecraft. A plan without the full infrastructure of a government agency could have liaison teams with members who each a responsible for handling contacts between a few other teams. Those liaison accomplices might — or might not — need to know the contextual details about the other teams, depending on the situation.

So communication between compartmentalized teams increases the complexity of the operation, sometimes by creating extra teams to facilitate those logistics. Similarly, perhaps other teams under Mr. C’s management are responsible for quality control. Such quality control teams could collect independent intelligence on the progress of primary teams, so the core conspirators can verify the work being done throughout the operation, and maintain assurance that it will succeed. Perhaps such teams would also be primarily responsible for neutralizing any leaks, or cutting teams loose if needed.

There would also sometimes be a need for entire contingency teams. As with military operations — and football plays — most projects include steps which are not entirely controllable and predictable. For many sub-projects and individual tasks, a backup plan can be developed in parallel. If a team running Plan A fails, then the conspirators can quickly pivot to activate Plan B using the backup team’s completed work. So some steps might be prepared more than once, from different angles, with different teams. Such teams could be aware or unaware, as needed. The greater the risks to witting participants, the greater the need for redundancies.

All accomplices in Tier 2 and lower may be witting or unwitting participants. Unwitting assets would have an understanding that they are working on something else. That cover plan could be something completely different than what’s happening, or even the exact opposite. Some unwitting accomplices might just be doing their job, performing fairly vanilla transactions.

Witting accomplices come in different flavors too, but Tier 2 and lower would never know the entire plan. It’s possible for Mr. A to explain some aspects of the larger plan to the team leader below him, so they logistically accomplish their responsibilities. Alternatively, Mr. A might need to vaguely explain some long-term goals of The Big Plan in order to motivate and impassion their team leaders to effectively manage sub-projects.

Perhaps Ms. B manages some witting accomplices to whom she also feeds a cover story. These people know that they are involved with something nefarious, illegal, risky, or at least confidential. But their sub-project may be framed in a totally different way to avoid sharing any additional knowledge about The Big Plan.

This could be similar to a bank heist plot where a team risks everything inside a bank without even knowing they’re really there to get some politically motivated document out of a box. Or when officials help cover-up for a rogue faction “for the good of the institution”. They are knowingly part of a conspiracy (e.g. the cover-up), while unaware of any larger conspiracy (e.g. the war).

Part 7: Other Model Clarifications

The more you compartmentalize, the more secure an operation may be. That does not necessarily make it a better operation. For example, “infinite security” is not an ideal goal.

Core conspirators — and accomplices on any level — would only recruit and select team leaders they can trust to get the job done and keep any secrets necessary. This is definitely another assumption in my model, and think it is generally true of most human organizing. Accomplices would also only be recruited if conspirators had confidence they had the moral fortitude — or lack thereof — to complete all their specific tasks.

As with any large organization, those making decisions at the top can have a whole spectrum of involvement with the gritty details of operations. Some CEOs read every report in the company and like to micromanage everything. Others stick with just delegating tasks to people who they expect to get the job done right and inform them if anything unplanned happens. Such heavily trusted accomplices could be like Frank Underwood’s right-hand-man in the TV show, House of Cards. Doug Stamper is Frank’s old friend and ally who almost intuitively knows how the core conspirator would make decisions in their shoes. Other heavily trusted accomplices could have a proven record of meticulously following their given orders, which are skills developed throughout military training.

When additional reassurance is needed, Mr. A could delegate separate quality control teams with equally important responsibilities of double-checking the work. If this is too much work or exposure for Mr. A, then he might just find a more competent leader for Team 2.A who can run both the main operation and also it’s separate supporting teams. If nothing else changed, then the chart would be updated to show Team 2.A with only one member. The right-hand man would responsible for tasks he can do alone, plus managing whatever teams needed (and possible). But even with a “team” of one, this compartment still provides an extra layer of firewall and plausible deniability, which are the main advantages of compartmentalization.

No matter the flavor, most heavily trusted accomplices would be witting. But below them, the general lack of preferences for blending witting and unwitting applies once again.

Model Parameters

I can think of no logical restriction on how many tiers deep an operation can go. Similar to individual team sizes, the number of tiers might be one useful unit of analysis. But I do not think these variables would be where any real-world operation design process begins or gets stuck.

For the sake of this compartmentalization model, I used a fixed size for each team/cell/compartment. This is just because it is dramatically easier to calculate and visually illustrate the strategy’s exponential impact.

I used the team size of five for how many motivated accomplices could reasonably keep a secret. I wanted to choose a number low enough for others to believe, even if they have the opposite confirmation bias delivering assumptions that conspiracies are rare or impossible.

One of the goals of this thought experiment was to extrapolate the compartmentalization model from a believably small team size all the way to the largest known conspiracy, around the orders of magnitude above 100,000 accomplices.

Appendix A: Trickle-Down Omissions

Omissions (neglected or withheld information) can be observed to trickle downhill, or layered like a nesting doll. For this thought experiment, let’s use a cartoon-level simplified version example of the Manhattan Project conspiracy. (This is not an attempt to make an accurate or even realistic organizational chart.)

Imagine if Mr. A was one of two core conspirators managing the top-level scientists. He would likely omit the fact that these weapons could effectively hold the world hostage. This means he would neglect to mention it when instructing his heavily trusted leader of Team 2.A — at least so it is not prominent in their mind.

Even if the Team 2.A Leader implicitly knows this, or figures it out, it’s definitely not part of his team’s mission. Leader 2.A would, in turn, omit any inkling they had about these risks when working with their team and all others.

So let’s presume Team 2.A knows that they are building nuclear weapons. But they never bring up nuclear weapons when collaborating with the Tier 3 Teams (3.A.A – 3.A.E). Instead, the Tier 3 Teams believe they are just building cool new conventional offensive weapons that are top secret. There might also be teams focused on allegedly defensive weapons research. But The Big Plan is now already inconceivable to most minds in Tier 3, because conventional weapons are very unlikely to alter the world order.

Then below them, there could be Tier 4 Teams (4.A.A.A – 4.A.E.E) who only work on the pure physical, chemical, and biological research. They would have no idea what types of technologies were being actively developed or deployed but might have inklings. They would rarely have any reason or ability to suspect a shift in the world order.

Then we could generalize the Tier 5 Teams (5.A.A.A.A – 5.A.E.E.E) as perhaps grounds maintenance staff, chefs, guards, etc. They would have even less reason or ability to suspect a shift in the world order.

But the big-picture cover story which everybody shared, was that they were developing classified military science aiming for peace. When a society’s language and logic are so inherently self-contradictory and Orwellian, then many cover stories that can mean anything to anyone.

| Likely to know? | Tier 1 | Tier 2 | Tier 3 | Tier 4 | Tier 5 |

| World Peace (*devil’s in the details) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Developing Classified Military Science | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Developing New Offensive Weapons | Yes | Yes | Yes | Inkling | Inkling |

| Developing Nuclear Weapons | Yes | Yes | Inkling | Inkling | Inkling |

| Entrenching The National Security State’s Position In The World Order | Yes | Unlikely | Unlikely | Unlikely | Unlikely |

Of course, U.S. citizens did not need to know, so they are not included in this table.

Appendix B: List of Reasons That Unwitting Accomplices Stay Silent

Intended to be a summary of Part 2 above, “Ways That Unwitting Accomplices Stay Silent”:

- No information access, need-to-know, omissions, compartmentalization

- Shared values [perceived], mutually shared goals, organic unity

- Accomplice recruited using a convincing cover story

- Cover story strengthens for the tragedy or accident’s aftermath

- Confirmation bias to see coincidence over conspiracy

- Painful cognitive dissonance in recognizing complicity

- Peer pressure, groupthink, Asch conformity experiments

- Simultaneous drills create earnest confusion

- Shame or fear to admit system failures or vulnerabilities

- Paycheck, budget, employment, career, professional reputation

- Following orders from an authority, Milgram experiments

- “Lone wolf” story is easier for media and police to sell and clean up

- “False flag” strategy actively intends to mislead investigations

- Media usually only covers straw man arguments for “conspiracy theories”

- Retaliation against whistleblowers, personal, legal, national security

- Blackmail by conspirators who document illicit or deviant behavior

- Physical or financial threats against one or one’s family

Appendix C: Book Recommendations

To dive deeper, you should definitely look for any public documents that intelligence agencies use to teach about compartmentalization, need to know, whatever they call it. Also, dive into first-hand accounts from participants in Manhattan Project. It’s been over a decade since I’ve read such books focused on the topics of compartmentalized organizations. But here are two suggestions with some gold:

National Security and Double Government, by Michael Glennon

“Why has U.S. security policy scarcely changed from the Bush to the Obama administration? National Security and Double Government offers a disquieting answer. Michael J. Glennon challenges the myth that U.S. security policy is still forged by America’s visible, “Madisonian institutions” – the President, Congress, and the courts. Their roles, he argues, have become largely illusory. Presidential control is now nominal, congressional oversight is dysfunctional, and judicial review is negligible. The book details the dramatic shift in power that has occurred from the Madisonian institutions to a concealed “Trumanite network” – the several hundred managers of the military, intelligence, diplomatic, and law enforcement agencies who are responsible for protecting the nation and who have come to operate largely immune from constitutional and electoral restraints. Reform efforts face daunting obstacles. Remedies within this new system of “double government” require the hollowed-out Madisonian institutions to exercise the very power that they lack. Meanwhile, reform initiatives from without confront the same pervasive political ignorance within the polity that has given rise to this duality. The book sounds a powerful warning about the need to resolve this dilemma-and the mortal threat posed to accountability, democracy, and personal freedom if double government persists. This paperback version features an Afterword that addresses the emerging danger posed by populist authoritarianism rejecting the notion that the security bureaucracy can or should be relied upon to block it.”

The Great Train Robbery, by Michael Crichton – classic tale of a meticulously planned conspiracy

Appendix D: Movie Recommendations

Here are some of my favorite movies and shows which dramatize some strategies which logically work for conspiracies. They might help you better visualize how such strategies are employed.

Secrecy (2008) — only documentary on this list

Executive Action (1973) – the most compelling visual illustration of how the JFK conspiracy might have occurred, YOU MUST SEE

Rubicon (2010) – best illustration ever of five powerful men with a national security conspiracy

Nick of Time (1995) – unwitting turned forced-witting

Shooter (2007) – unwitting accomplice turned patsy

The Parallax View (1974) – quasi-witting accomplice

The Manchurian Candidate (1962 and 2004) – Project MKUltra research-related, mind-control level unwitting accomplices

The East (2013) – a private intelligence operative infiltrating anarchist group

The Good Shepherd (2006) – insightful dramatization surrounding birth of CIA

Wag The Dog (1997) – “Shortly before an election, a spin-doctor and a Hollywood producer join efforts to fabricate a war in order to cover-up a Presidential sex scandal.”

The Americans (2013) – TV series with tons of examples of older intelligence tradecraft

The Great Train Robbery (1978 or 2013) – lovely film adaptations

Eyes Wide Shut (1999) – example of an esoteric recruiting process into a deeper layer of society